Suicidality is a complex, multi-contextual human experience that affects millions of people every year in the United States (U.S.) (CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention & National Center for Health Statistics, 2021). It is estimated that nearly 48,000 adults and youth have died by suicide, 1.2 million adults ages 18+ have attempted suicide, 3.2 million adults ages 18+ have made suicide plans, and 12.2 million adults ages 18+ have seriously thought about suicide in the last year (CDC, 2023; Curtin et al., 2022). Although pervasive, suicidality disproportionately impacts a range of communities who face a range of unique individual-in-contexts challenges, such as American Indian/Alaska Native populations (CDC, 2022; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [HHS], 2024), LGBTQIA+ youth (CDC, 2021b; Gorse, 2022), military veterans (Department of Veteran’s Affairs, 2022), incarcerated individuals (Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2021), youth involved in the child welfare systems (Brown, 2020; Hochhauser et al., 2020), and people living in poverty (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2022; Wang & Wu, 2021). Moreover, many ethno-racially minoritized groups with historically low suicide rates have experienced significant increases. Stone et al. (2023) reported that age-adjusted suicide rates among Hispanic communities increased 6.8% between 2018 and 2021. According to these same authors, the overall suicide rates in Black populations grew by 19.2% during the same period and significantly escalated among Black people ages 10 to 24 (36.6%).

Suicidality in Black Communities

The increasing suicide rates in U.S. Black communities underscore the need to examine and address oppressive individual-in-contexts forces (Hightower, 2022; Hightower et al., 2023). According to the CDC (2022), “Suicide and suicidal behavior are influenced by negative conditions in which people live, play, work, and learn” (para. 2). These negative conditions, like cultural, organizational, interpersonal, and intrapersonal forms of racism disproportionately affect—and have harmed—Black communities (K. Alvarez et al., 2022; Johns Hopkins Center for Gun Violence Solutions & Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Department of Mental Health, 2023; Sheftall et al., 2022). These multi-contextual harms seem to be reflected in the Black suicide mortality data spanning the last twenty-five years. Al-Mateen and Rogers (2018) revealed that deaths by suicide among Black female youth increased 182% between 2001 and 2017. During this same period, the authors reported a 60% increase in Black male teen suicide rates. Moreover, Bridge et al. (2018) discovered that, compared to White cohorts between the ages of 5 and 12, similarly-aged Black cohorts’ suicide rates were nearly double. In the subsequent four years since these arresting trends were revealed, Bommersbach et al. (2022) noted that the likelihood of Black adult suicide attempts was greater in the past year. Also, Sheftall et al. (2022) documented that Black high school adolescents experienced the largest increase in deaths by suicide compared to other racially diverse populations in similar age groups. Such discoveries indicate that Black suicidality and its related harms occur significantly across the life span.

Overwhelmingly, Black deaths by suicide involved extremely lethal means and occurred in multiple, oppressive contexts (K. Alvarez et al., 2022; English et al., 2024; Sheftall et al., 2022). These contexts generally included risk factors such as being resource deprived, having limited access to formal and informal social supports, experiencing a pervasive lack of control in one’s life, and feeling indefinitely trapped (HHS, 2024; Jewett et al., 2024; Tanne, 2024). Moreover, deaths by suicide in Black communities occur in the additional contexts of the United States’ violent legacies: African enslavement, Caribbean colonization, and the perpetuation of intra- and inter-generational trauma (Alexander, 2020; Henderson et al., 2021; Kendi, 2016, 2019; Longman-Mills et al., 2019). New suicidology frameworks are needed to illuminate individual-in-contexts’ factors that contribute to suicidality in Black communities more fully. Such models would enable human services professionals to better conceptualize and address suicide (Westefeld & Rinaldi, 2018). This article proposes the Individual-in-Contexts Model (ICM), which attempts to address the limitations of traditional psychological and public health approaches by integrating critical and ecological systems perspectives. Once described, the article explores the ICM’s application to suicide screening, assessment, and intervention processes in Black communities. Finally, we propose ICM-inspired research, practice, and policy recommendations.

Critical, Ecological, and Contextual Perspectives: The Foundations of the Individual-in-Contexts Model

Suicidality always involves people. Simultaneously, it always occurs at specific times, in particular places, and under certain circumstances. These realities require a framework that address the interplay between individuals and their contexts. Critical suicide studies’ emphases on socially unjust contexts and marginalized lived experiences illuminate relationships among people, their intersectional identities, the environments in which they are situated, and suicide (Hightower, 2022; Hightower et al., 2023; Marsh, 2020; Standley, 2022). While this school of thought offers important analytical tools for understanding connections between social injustices and suicidality, it has not yet offered an explicit approach for suicide screening, assessment, or intervention in Black communities.

Although critical suicide studies highlight the ways oppression—like racism, ableism, and homophobia—influence suicidality, it does not provide a specific model for researchers, clinicians, or policy-makers to systemically conceptualize or address suicidal experiences. Moreover, the social work profession’s person-in-environment model offers a useful general understanding of the interdependence between human beings and their social milieu. However, this model often neglects the significance of geographic locations and the physical environments that influence people’s suicidality (Akesson et al., 2017). These conceptual limitations are better addressed by ecological systems frameworks.

Bronfenbrenner (1994) asserted in his ecological systems theory that individual experiences affect and are affected by interactions among people and five nested systems: micro- (close relationships), meso- (interactions among close relationships), exo- (direct and indirect community forces), macro- (political, social and cultural dynamics), and chrono- (historical and developmental influences) systems. Building on Bronfenbrenner’s model, Ballou et al. (2002) developed a feminist ecological systems theory. This framework includes an examination of planetary (the natural environment) factors and intersectional power dynamics that affect all human experiences.

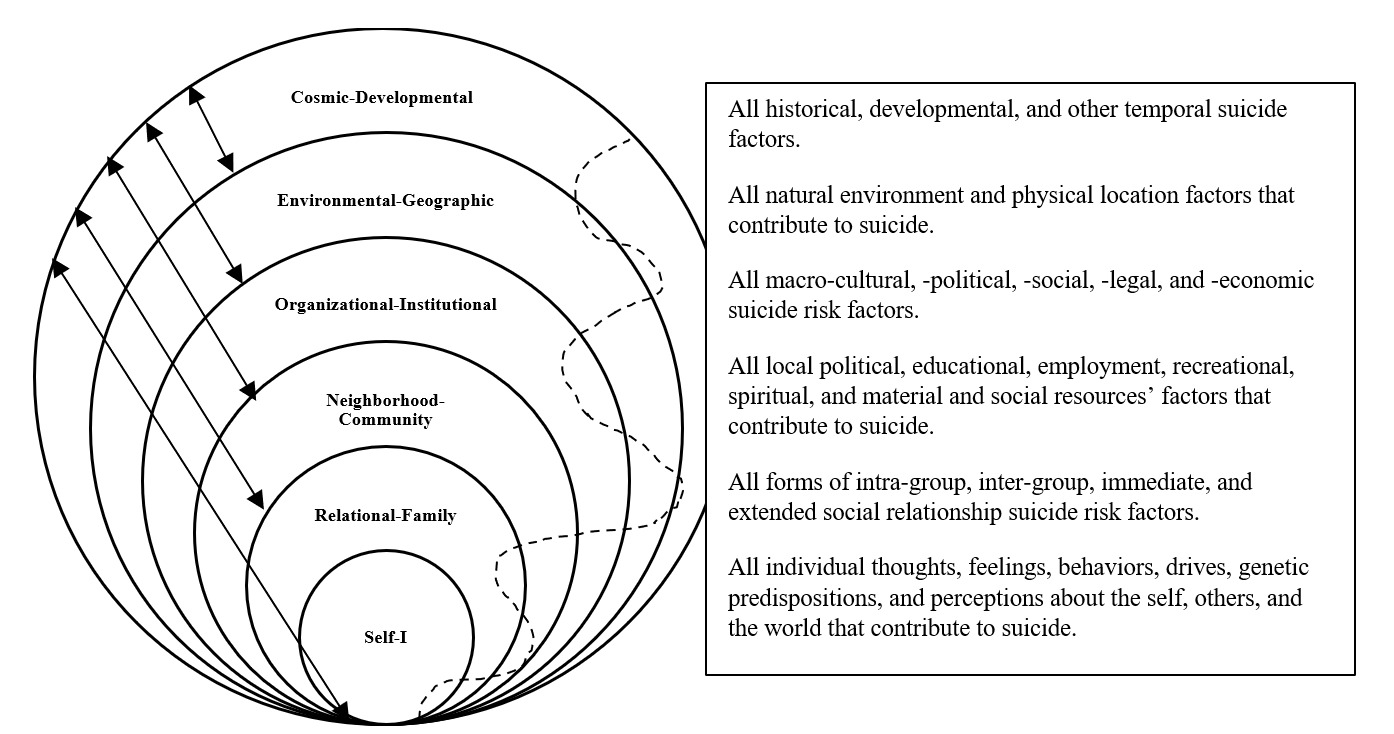

While ecological systems theoretical constructs broaden human services professionals’ ability to conceptualize human experiences more complexly, application issues persist. One problem is the language used related to ecological concepts. The prefixes micro-, meso-, exo-, macro-, and chrono- obscure the meaning of these constructs and their usefulness to human services practice. Another shortcoming of these models is the fact that these frameworks, despite being visually depicted as nested and interactive, seem to be discrete monolithic concepts. For example, the term chrono-system encompasses myriad historical, developmental, and temporal forces, yet the term minimizes that complexity with its single label. In response to these shortcomings, Schalock et al. (2020) postulated a context paradigm “that focuses on the interrelated conditions that surround the phenomenon being examined” (p. 2). Such a model highlights “the totality of circumstances that comprise the milieu of human life and human functioning” (Shogren et al., 2014, p. 110). The proposed model—the Individual-in-Contexts Model (ICM)—draws conceptual inspiration from critical, ecological, and contextual perspectives. Figure 1 illustrates the ICM and defines its core interrelated concepts.

The ICM expands the number of systems to six hyphenated contexts. Hyphens are used to connect and signify infinite spaces along conceptual continua. These constructs—and examples of context-specific suicide risk factors placed in parentheses—include: Cosmic-Developmental (historical legacies of oppression and developmental concerns), Environmental-Geographic (pollution exposure and natural resource-deprived locations), Organizational-Institutional (macro-oppressive laws and -economic inequities), Neighborhood-Community (community violence exposure and local poverty rates), Relational-Family (social isolation and interpersonal discrimination), and Self-I (ascribed marginalized identities and internalized self-harming thoughts, feelings, and behaviors). Moreover, the use of lines further reinforces inter-contextual relatedness. The double-arrowed lines emphasize between-contexts dynamics. For example, an individual (Self-I) shapes their family (Relational-Family) contexts and those same family contexts influence the individual. Additionally, the broken line represents the intersectional experiences of privilege and oppression that manifest within and across contexts. For instance, a Black cisgender gay man enjoys gender privileges in most contexts, yet also experiences varying degrees of disadvantage within and across anti-Black and anti-LGBTQI+ contexts. In tandem, the concepts that comprise the ICM better underscore suicide risk factors’ interrelated dynamics within and across contexts. Finally, while this framework may be germane to all suicide-vulnerable people, the remainder of this article describes ways the Individual-in-Contexts Model (ICM) and its concepts might be used to screen for, assess, and intervene with suicidality in Black communities.

The Individual-in-Contexts Model (ICM) and Suicide in Black Communities

The ongoing construction of Black racial identities has shaped, and continues to influence, Black people’s views of themselves—past, present, future, strengths, and vulnerabilities. These views exist, and are informed by, myriad interconnected contexts that Black communities emerge from, evolve in, contribute to, and are affected by. This section details the dynamic and complex intersections among Black identities, contextual forces, and suicidality (English et al., 2024; Finigan-Carr & Sharpe, 2024; HHS, 2024). These intersections highlight the importance of a Black individual-in-contexts model to better understand deaths by suicide.

Cosmic-Developmental Contexts

All anti-Black forces that contribute to suicide began, evolved, and continue to unfold across specific moments in time. Understanding Cosmic-Developmental influences on deaths by suicide in Black communities clarifies links to historical and intergenerational forms of trauma, and life course stages (Yates et al., 2024). This temporal analysis also fosters an examination of White supremacist dominant culture, historical time, trauma exposure, developmental experiences, anti-Black policies, and suicidality intersections (English et al., 2024). For example, in the 1980s—during the height of the HIV/AIDS crisis—Black LGBTQIA+ cohorts experienced compounded harm related to the confluence of anti-Black, anti-gay, and politically-conservative forces embedded in that decade. These cohorts were invisible in terms of public health prevention campaigns, and were typically excluded from predominantly White gay activist groups (Simone, 2012). Their invisibility and powerlessness were rooted in—and can only be understood by examining—those Cosmic-Developmental, anti-Black, anti-gay, and conservative political contextual intersections. A similar dynamic may also help explain the current increase in suicidality among many Black youth and emerging adult populations. These groups have been exposed to innumerable forms of highly publicized anti-Black violence and ongoing anti-Black social forces for decades (K. Alvarez et al., 2022; Braithwaite & Graham, 2023).

Environmental-Geographic Contexts

Because the planet’s atmosphere, geography, and natural resources all enable human social contexts to exist, planetary or climatic changes invariably affect human functioning and thriving. Dumont et al. (2020) noted that air pollution and global temperature increases due to human lifestyle and economic activities correlate with increased suicide risk. The same authors stressed that indigenous and marginalized communities are—and will be—disproportionately affected by environmental-geographic risk factors. This reality has implications for suicides in Black communities.

Due to racist Jim Crow housing and urban development policies, Black communities are frequently located near carbon dioxide producing highways, factories, and waste storage and treatment facilities (C. H. Alvarez & Rosenfeld Evans, 2021). Such disproportionate exposure to environmental hazards likely compounds Black community suicide risks. Moreover, Reuben et al. (2022) developed an evidenced-based conceptual model highlighting the interplay among environmental toxins, stressors, natural disasters, individual and community biopsychosocial declines, and structural inequities such as anti-Black racist policies.

Organizational-Institutional Contexts

Organizational-Institutional contexts reflect the time periods in which they emerged, as well as the physical locations in which they are situated. These contexts embody the human-constructed cultural, political, and economic scaffolding that shapes societal experiences and understandings. Embedded in each context is an institutionalized form of oppression and privilege that governs the distribution of resources and opportunities (Tanne, 2024; Wang & Wu, 2021). Such distribution is neither equal nor equitable (Kendi, 2019). Additionally, these experiences and understandings emerge through interactions with institutions like churches, mosques, synagogues, schools, media, legislative bodies, civic groups, government agencies, professional associations, and financial organizations. Through such interactions, people internalize values, beliefs, and expectations about themselves, other people, and the world. These beliefs often manifest in complex emotional and behavior patterns that are context- and relationship-specific (Joy, 2019).

For instance, to understand a Black woman’s death by suicide, one must understand where she is positioned in history and human development. That understanding must also consider the natural world she occupies at the specific time she died by suicide. Furthermore, such time and location considerations affect and are affected by intersectional Organizational-Institutional factors, like gendered racism. This interconnected and macro-contextual analysis is crucial for understanding the upstream—and often obscured—factors that contribute to Black deaths like suicide.

Neighborhood-Community Contexts

Organizational-Institutional forces such as U.S. constitutional laws, free market capitalism, and systems of privilege and oppression flow downstream to influence local neighborhood and community experiences. For example, local zoning laws, school policies, and policing practices disproportionately harm Black communities via rent price gouging, poorly funded schools, and state-supported violence (Braithwaite & Graham, 2023; English et al., 2024; Semenza et al., 2024). The primary differences between Neighborhood-Community and Organizational-Institutional contexts pertain to scale, scope, and proximity. The latter contexts operate broadly and distally across an entire society, whereas the former contexts function narrowly and proximately. While these contexts interact and mutually influence one another, neighborhood-community contexts more frequently and directly affect inhabitants’ daily experiences. Such experiences are likely to include town residents noticing the influences of local government, city commerce, and community human services because contact with these entities occurs regularly. Local contacts, or the lack thereof, can contribute to anti-Black neighborhood-community forces that magnify suicide risk among Black communities. Examples include anti-Black local law enforcement, segregated and ghettoized neighborhoods, city unemployment, and town poverty—all typically contribute to and/or compound the conditions associated with suicidality (K. Alvarez et al., 2022; Braithwaite & Graham, 2023; HHS, 2024; Sheftall et al., 2022).

Relational-Family Contexts

The Relational-Family contexts dimension of this model emphasizes the power—both the wellness and damaging potential—of intimate human connections. Human beings are social and require secure-enough attachments to survive and thrive (Bowlby, 1998; HHS, 2024). In these contexts, minoritized identity-based threats to safe social connections—like teasing, bullying, and/or abuse—frequently accelerate the suicidal ideation-to-action progression that originated upstream from overarching contextual forces (Richardson et al., 2024; Sigurnvinsdottir et al., 2020). One instance of this dynamic would be a queer Black child harassed at school for being Black (Neighborhood-Community) and abused at home for being queer (Relational-Family). The young person may experience an amplified suicide risk due to this interactive effect. The Trevor Project (2023) reported that among Black cisgender LGBQ, transgender, and non-binary young people, 67% experienced discrimination, 31% were physically threatened or harmed, 59% experienced attempts by others to change their identities, and 29% described identity-related housing instability: all suicide risk factors. Moreover, Shadick et al. (2015) confirmed that Black LGB college students who experienced racialized harassment at school and homophobia at home reported greater levels of suicidal ideation than their White, heterosexual, and cisgender counterparts. Within relational-family contexts, it is essential to assess and address connections between intra- and inter-contexual oppression and suicide to prevent Black deaths.

Self-I Context

This dimension of the ICM describes the furthest downstream point and most individualized level of the model. The Self is an innate, intrapsychic presence. This component refers to a person’s inner sense of authenticity (Schwartz, 2023). For example, the statement “I am Black” is a particular description of one’s personhood. At the other end of the continuum is the I. The I reflects the interplay of all the other contextual forces and an individual’s overall bio-psycho-social-spiritual appraisal of themselves. For example, a person who believes, “Based on the feedback I have received from news media, classmates, and my family about being Black and queer, I think I am worthless.” This confluence reveals the unique, nuanced, dynamic, and complex realities individuals experience—and make meaning of—from birth to death that contribute to suicidality. Thus, to prevent individual suicides in Black communities, clinicians, researchers, policymakers, and the public-at-large must understand the interactions within and across contexts that generate and perpetuate suicide-vulnerability. Increases in harmful contextual forces and marginalizing people’s identities would likely increase suicidality. Conversely, affirming contextual forces and cultivating an appreciation of diversity would likely reduce suicide risk (The Trevor Project, 2023).

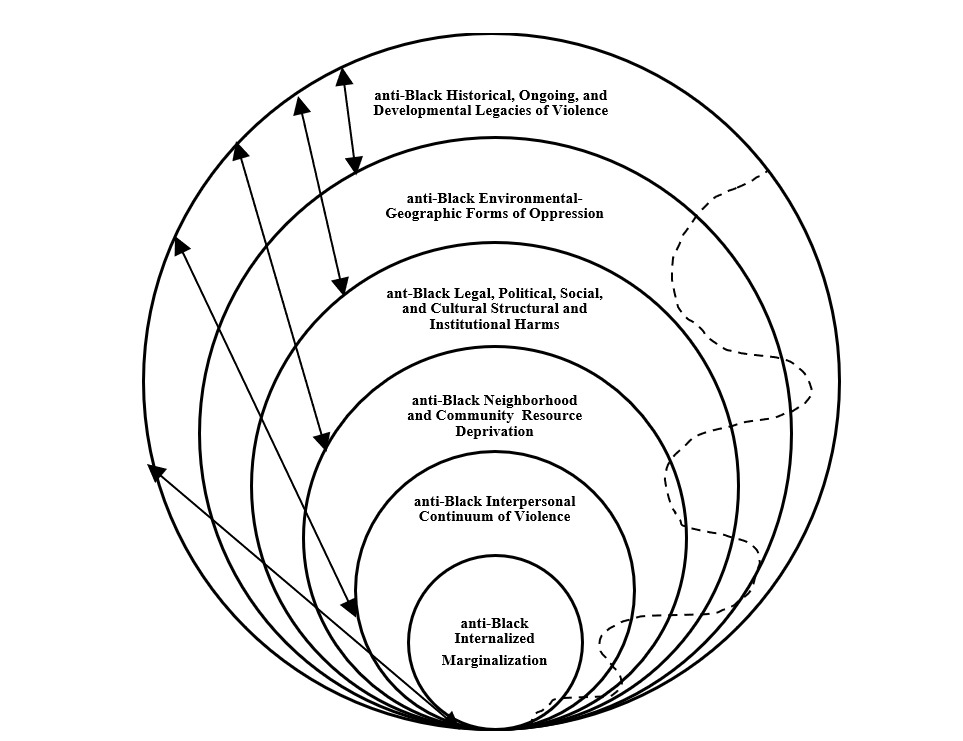

While the ICM can be used to illuminate the myriad interplays among contextual forces, identities, and suicidality, Figure 2 depicts the ICM as it relates to anti-Black, inter-contextual, suicide-contributing forces.

The ICM and Suicide Screening, Assessment, and Intervention in Black Communities

From the moment in time that human populations developed and spread anti-Black, violent, and oppressive contexts across the globe, Black communities around the world have endured detrimental effects (Kendi, 2016; Longman-Mills et al., 2019; Snyder, 2015). Such contexts have contributed to historical trauma, eco-racism, global eco-migration crises among Black peoples, racialized public policies, resource-deprived communities, violent interpersonal relationships, and suicide-vulnerable individuals (Kendi, 2019; Tubert, 2021; Yates et al., 2024). As identity-based, power-over dynamics manifest within and flow across each human context, harms compound, especially when they are internalized by individuals and communities with multiple minoritized identities (English et al., 2024; Jewett et al., 2024; Joy, 2019). When viewed from this vantage point, the term suicide—and the common narratives about its meanings, causes, and implications—must be critically re-interrogated and re-imaged to decrease suffering, improve lives, and prevent suicides that can be prevented. To that end, Tables 1, 2, and 3 offer templates for reimagined, ICM-inspired suicide screening and assessment questions, and intervention strategies. The screening and assessment questions are simply descriptive: they are designed to encourage human services providers and decision-makers to conceptualize suicidality in more complex and contextual ways.

ICM Screening in Black Communities

Most medical, psychosocial, and public health screenings are designed to rapidly establish the presence or absence of a specific condition. Suicidality screening tools overwhelmingly include five to ten yes/no questions that focus on individual-level ideation, intent, plan development, access to means, and capability to use intended means (Christensen LeCloux et al., 2022; Quinlivan et al., 2016). While such screening questions likely help clinicians and other decision-makers determine some people’s immediate individual-level risk, contextual suicidality-contributing forces are frequently overlooked. This oversight has serious suicide prevention implications. Bryan (2021) and Millner et al. (2017) both noted that the continuum of suicidality ideation-to-action is dynamic: distal and proximate suicide-potentiating factors often shift rapidly. This pattern illuminates the reality that seemingly distal and contextual experiences—such as seeing or hearing about resource deprived, or overly-policed communities with easy access to guns—may quickly catalyze suicidality in Black communities already harmed by legacies of violence and oppression. Furthermore, screening question results often shape human services decision-makers’ choices about who receives access to more in-depth assessments or concrete interventions, like financial assistance, a mental health referral, and/or medical care. Thus, ICM screening questions like the ones described in Table 1 better reveal the contextual forces that contribute to suicidality than traditional screenings that typically ignore contextual experiences. These revelations also must be emphasized in in-depth suicide assessments of Black community members.

ICM Assessment in Black Communities

For most of the 21st century, psychiatry and psychology have dominated suicidology discourses and research about suicide assessment and intervention (Hightower, 2022; Hjelmeland, 2016; Marsh, 2010, 2016, 2020; Tatz & Tatz, 2019). These fields of study typically conceptualize suicide in individual, decontextualized, apolitical, and biomedical terms (Button, 2020; Marsh, 2020). This conceptualization emerges from theories that narrowly focus on some combination of maladaptive intrapsychic forces, distorted cognitions, dysregulated affective states, and/or harmful behaviors. However, like traditional screenings, typical assessments focus on individual-level psychopathology and ignore the macro-contextual factors in which the individual are situated. In fact, Bryan (2021) noted that “the actual rate of diagnosed mental illness among suicide decedents [is] . . . around 45%” (p. 46). This insight raises critical questions about the suicide-contributing factors associated with the estimated 55% of deaths by suicide that do not involve a mental health condition, especially among minoritized peoples like Black communities. The ICM assessment questions described in Table 2 encourage human services practitioners and leaders to explore in-depth the multi-contextual experiences of Black community members. This exploration is essential for accurately conceptualizing the degrees to which suicidality in Black communities results from untreated mental illness and/or unaddressed anti-Black historical, political, and social pathologies. This more accurate reframing would likely generate new suicide prevention and intervention efforts specific to Black communities.

ICM Interventions

Ideally, suicide screening questions accurately detect the presence of suicidality risk and assessments reveal the breadth and depth of that risk. Human services professionals should use information gathered from both processes to develop interventions. Table 3 describes interventions that address multi-contextual suicide-contributing factors in Black communities. The interventions described offer context-specific strategies that plausibly offer benefits across contexts. For example, truth, justice, and reparations efforts would undoubtedly improve Black communities’ material social and economic conditions, as well as address many historical and intergenerational harms. Moreover, such improvements would probably amplify the benefits of specific interventions within each of those contexts as well. Monetary reparations that address anti-Black legacies—coupled with individual-level psycho-social skill building—would likely increase the probability of achieving one of suicidology’s central goals: to help people create lives worth living for. The ICM framing of interventions flows from the model’s underlying assumption that suicide is complex and multi-contextual in nature. This assumption is more likely for minoritized groups—like Black communities—because traditional models have not resulted in lower suicide rates for these cohorts recently (K. Alvarez et al., 2022; Stone et al., 2023). Such framing and assumption-making have implications for human services research, practice, and policy development.

ICM Implications for Human Services Research, Practice, and Policy-Making

The ICM integrates critical, ecological, and contextual theories, and Black communities’ historical and contemporary lived experiences. This integration builds on traditional psychological theories, public health recommendations, sociological perspectives, critical suicide studies’ research, and Black feminist scholarship. Such interdisciplinary synthesis has implications for future research, practice, and policy-making.

Future quantitative research needs to assess the statistical validity and reliability of suicide prevention screening tools, assessment protocols, and interventions that attempt to holistically conceptualize suicidality as the complex, multi-contextual experience it is—specifically among Black communities. Furthermore, qualitative research is needed to explore Black communities’ experiences with current suicide prevention efforts, perspectives about community-specific suicide-contributing factors, and insights about ethnoculturally-centered suicide prevention and intervention strategies (HHS, 2024). These research efforts should be conducted by collaborative, interdisciplinary, and multi-racial coalitions of scholars, activists, and community members with minoritized and suicide-lived experiences. Such efforts may mitigate ethnocultural insider-outsider biases, and amplify diverse, intersectional, and integrative knowledge-generation, -interpretation, and -application paradigms.

In addition to inspiring future research, the ICM may catalyze suicide prevention practice changes. Human services professionals such as social workers, licensed mental health counselors, psychologists, and psychiatrists provide most of the mental health services, and thus suicide prevention care, in the United States (Heisler, 2018). However, these professionals face a two-pronged problem. Most psychosocial professionals receive little to no training in suicide prevention (Mirick et al., 2020; Ruth et al., 2012). Moreover, these same professionals lack cultural humility training because psychosocial professions historically have been complicit in minoritized communities’ oppression (Aguilar & Counselman-Carpenter, 2021; DeAngelis & Andoh, 2022). The proposed model—the ICM—addresses these challenges by combining multi-contextual, suicide screening, assessment, and intervention training with intersectional analytical tools to better conceptualize suicide prevention-cultural humility, specifically in Black communities. To ensure culturally-appropriate suicide prevention in Black communities is delivered, psychosocial training and accrediting organizations ought to consider mandating universal, culturally-relevant suicide screening, assessment, and intervention course work and continuing education requirements (Hightower et al., 2023). Such mandates would likely save more lives, especially in Black, and other minoritized communities.

Finally, the ICM promotes multiple policy reforms. To address historical, ongoing, and inter-contextual anti-Black legacies that contribute to suicidality, organizational and institutional changes are necessary (English et al., 2024; Finigan-Carr & Sharpe, 2024: Jewett et al., 2024; Yates et al., 2024). The ICM offers a framework for both interrogating contextual injustices and reimagining ways to promote justice, equity, and inclusion for Black communities through policy initiatives, such as reparations. Furthermore, the ICM illustrates the need for suicide prevention organizations and advocacy groups to promote policy statements that center and explicate the fact that anti-Black racism, and other forms of identity-based violence, contribute to deaths by suicide. Lastly, the ICM offers a rationale for policy-makers and stakeholders to collaboratively develop the means for evaluating public policies in terms of its suicide-potentiating impacts on Black communities, and other vulnerable populations. Policy harms and benefits would have to be equitably resolved before it could be passed. In concert, the ICM offers a perspective that may positively contribute to research, practice, and policy advances that save more Black lives by more holistically screening for, assessing, and addressing the continuum of suicidality-potentiating factors in Black communities.

Conclusion

Suicide is almost universally recognized as a complex human experience that affects millions of people world-wide every year. Despite this acknowledgement, most suicidology research, practice, and policy-making are influenced by few fields of study: mostly psychiatry and clinical psychology (Marsh, 2010, 2016, 2020). Such influence has been used to frame suicide as a predominantly individual, apolitical, biomedical, and decontextualized problem (Button, 2020; Marsh, 2020). This framing’s narrow focus results in interventions that attempt to modify or control individual thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. More recently, the field of public health has contributed to suicidology by focusing on population-level prevention. While traditional suicidology theories and public health paradigms have undoubtedly saved some lives, suicide rates in Black and other minoritized communities continue to increase (Baril, 2023). However, none of these disciplines typically frame suicide in critical, intersectional, social justice, or contextual terms.

The Individual-in-Contexts Model (ICM) integrates a variety of perspectives germane to minoritized groups, like Black communities. Such an integrative model expands and deepens human services researcher, provider, and policy-maker thinking about holistic suicide screening, assessment, and intervention in Black communities. New models, like the ICM, are needed to guide future intersectional research questions, improve screening validity, and bolster assessment accuracy in hopes of reducing suicide deaths among Black peoples, and other minoritized groups. Finally, the ICM also illuminates the need to address the United States’ legacies of anti-Black policies, as well as the need to develop evaluative tools to assess the oppressive-potential of future legislation.

Authors

Heath H. Hightower, Ph.D., DCSW, LICSW is an assistant professor in social work and equitable community practice and a clinician of twenty-six years whose research and clinical work focus on the intersections of identity, harmful systemic forces, suicidality, and mental health experiences. University of Saint Joseph, Social Work and Equitable Community Practice, 1678 Asylum Avenue, West Hartford, CT 06117, hhightower@usj.edu

Morgan J. Grant, Ph.D., MS, MBA, CHES, CPH recently completed his doctorate at Texas A&M University School of Public Health and is research fellow in the Center for Health Equity and Evaluation Research. His research interests focus on mental health and suicide in at-risk and minority populations, with special emphasis on LGBTQ+ and Black adolescents. Department of Health Behavior, School of Public Health, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX 77843

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. Joanna Almeida and Dr. Sonya Carson for reviewing this manuscript and offering feedback.