Introduction

Recovery High Schools (RHS) serve as specialized educational environments, that often hire and partner with human services organizations and providers, designed to support adolescents recovering from substance use disorder (SUD). RHS provide unique environments to holistically support students during a vulnerable time after receiving treatment for substance use (R. Oser et al., 2016). RHS have been becoming more popular in recent decades as a suitable recovery option for adolescents with 42 recovery high schools now in the United States and more currently in development (Recovery Research Institute, n.d.). The research in this field is growing, but there has been little research regarding the human services (ie., social workers, counselors, mental and behavioral health specialist, program director) staff and other professional staff , such as teachers and school leadership that provide education, care, and services to the adolescent students attending RHS. Staff may be at risk for compassion fatigue and burnout and may experience challenges in their work engagement (Bakker & Demerouti, 2007; C. B. Oser et al., 2013; Perkins & Sprang, 2013). These risks may be influenced by organizational factors, their own personal trauma history, and their own substance use recovery experiences (Knudsen, 2009). It is important to explore the dynamics of human services and non-human services staff working in the specialized environments of RHS to better understand RHS staff characteristics to inform staff and their leadership, who are both in prime positions to affect RHS students’ academic and recovery journeys. Given the unique mission of these specialized schools, and the criteria for adolescent student admission, it was important to examine if there could be differences. Human services staff in these settings are working directly with these students, who we argue are advancing RHS missions that typically involve a focus on students’ sobriety.

RHS staff are an essential component of the recovery process for adolescents attending recovery schools. They play a critical role in fostering a supportive and nurturing environment that promotes academic success and long-term recovery. The cohesive support network comprised of educators, administrators and professionals allows RHS to address academic, emotional, and social needs of students in a healthy organizational environment. Research has shown that organizational factors, such as staff support, process quality improvements like Plan, Do, Study, Act (i.e., PDSA), and positive supervisory experiences among counseling staff have been shown to boost staff resilience, reduce compassion fatigue and positively impact organizational processes (B. E. Bride et al., 2007; Kapoulitsas & Corcoran, 2015; Rieckmann et al., 2011). This suggests that RHS staff who have adequate organizational support can have a better professional quality of life. Understanding RHS staff characteristics can enhance the effectiveness of recovery school programs, ensuring that they offer the best possible support for adolescents on their path to recovery.

This study sought to determine staff wellbeing or professional quality of life with particular attention to compassion fatigue and satisfaction, burnout, perceived social support, and staff work engagement. Therefore, we examined:

-

What is the professional quality of life (compassion satisfaction, compassion fatigue, burnout, secondary trauma) of RHS behavioral health staff?

-

What is the work engagement (vigor, dedication, absorption) of RHS behavioral health staff? What is the perceived social support of RHS behavioral health staff?

-

Is there an association between RHS behavioral health staff professional quality of life, perceived social support, and work engagement?

-

What are study results implications for leadership?

This study also analyzed the staff’s personal characteristics that might influence the results, specifically adverse childhood experiences (ACE) and substance use history. This research contributes valuable insights as, to the author’s knowledge, there are no known studies that examine RHS staff characteristics with implications for staff and leadership. The authors sought to contribute to the growing body of literature regarding RHS and explore the staff workers in recovery-focused educational settings and any characteristics of the staff that might affect the adolescent students.

Literature Review

Recovery High Schools

RHS are an alternative school environment for teens struggling with substance abuse disorder (SUD) that provides post-treatment education and support (Finch et al., 2018; Hennessy & Finch, 2019; Tanner-Smith et al., 2018; Viverette et al., 2020). SUD is defined as a disorder that interferes with an individual’s mind and behavior due to the inability to control the use of their substance (NIMH, 2023). Adolescents are especially susceptible to relapse after leaving treatment; however, RHS provide a buffer that offers academic and therapeutic support, as well as prosocial peers who are also on their recovery journey (Bowie-Viverette et al., 2024; Finch et al., 2018; Hennessy & Finch, 2019; Tanner-Smith et al., 2018). This form of continuing care supports the vulnerable population of adolescent substance users who are at risk of relapse and/or dropping out of school (Finch et al., 2018; Tanner-Smith et al., 2018). The staff that make up a RHS typically consists of regular school staff such as administration and teachers, but additional employees can include recovery support specialists, substance use counselors and mental health professionals, who we refer to as staff and professionals (Association of Recovery Schools, n.d.). These specialized schools employ human services professionals, who are defined as: “uniquely approaching the objective of meeting human needs through an interdisciplinary knowledge base, focusing on prevention as well as remediation of problems, and maintaining a commitment to improving the overall quality of life of service populations” (National Organization for Human Services, n.d.). This includes RHS school leadership as they are required to be equipped to lead and manage adolescent students in recovery, which differs from the mission and focus of traditional school settings (Barnetz & Vardi, 2015; Bowie-Viverette et al., 2024). This study will examine the qualities of recovery school professionals in the RHS setting.

Adverse Childhood Experiences

Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) relate to a variety of unfavorable or negative events that occurred in someone’s life before the age of 18 (Brown et al., 2022). ACE can be related to abuse, substances, or adversity within the home. Individuals with higher ACE scores are more likely to experience mental health and other health challenges later in life. In one study conducted by Brown and associates (2022), it was determined that helping professions and trauma-related professions commonly have higher rates of ACE and trauma than the general population. Social work and counselor study participants often had higher rates of ACE, making them more susceptible to mental health problems (Brown et al., 2022). Higher ACE scores were also associated with higher rates of burnout and compassion fatigue (Brown et al., 2022).

Substance Use Disorder

SUD is the inability to control substance use that negatively affects the individual using (NIMH, 2023). According to American Addiction Centers (2024), over 46 million Americans struggled with SUD in 2022. In 2023, 8.5%, or 2.2 million, American adolescents had a substance use disorder (SAMHSA, 2024). There is currently no literature examining the substance use history on professionals who are working with adolescent students in RHS. This study will shed some light on the intricacies of these two subjects and how recovery may impact professionals in their work lives.

Professional Quality of Life

Professional Quality of Life is characterized by how an individual feels about their place within their work as well as the quality of their work (Tran et al., 2023). It is comprised of two main concepts, compassion satisfaction and compassion fatigue (Tran et al., 2023). Compassion satisfaction is the reward feeling an individual gets from helping others (Cetrano et al., 2017). Compassion fatigue, comprised of secondary traumatic stress (STS) and burnout, is almost the opposite; it is the depleted capacity of the professional to be empathetic (Cetrano et al., 2017). Many factors can play into these quality-of-life factors; and a variety of professions can experience both compassion satisfaction and compassion fatigue. Research shows that one of the factors that positively affects professional quality of life is supportive and open leadership (Parry et al., 2023). The working environment is vital to supporting a healthy professional quality of life. Leadership has a large impact on professionals and can influence them either positively or negatively. Other factors include positive peer support, available resources, and work-life balance (Cetrano et al., 2017; Parry et al., 2023; Turkington et al., 2023). Having a strong sense of compassion satisfaction positively affects workers motivation as well as work engagement and contributes to a healthy professional quality of life (Cetrano et al., 2017). This is especially important in human services and school settings.

The more prominent professions discussed in relation to the study concepts include healthcare professionals, teachers, social workers, mental healthcare professionals, and substance abuse professionals. Mental health care professionals tend to have lower job satisfaction and thus lower professional quality of life (Parry et al., 2023) and substance use professionals have been shown to have high levels of work stress, burnout, and low work satisfaction as well as lower professional quality of life (Beitel et al., 2018; Broome et al., 2009; Johannessen et al., 2021). In addition to this strain on both substance use and mental health, or behavioral health, professionals, those working with adolescents or younger populations reported experiencing emotional exhaustion from their work (Parry et al., 2023). For professionals, working in a setting that provides multifaceted support to adolescent students, who deal with a variety of issues including mental health and substance abuse, we can infer that there may be similar trends present. However, there were no studies found that focused on this among RHS staff.

Compassion Fatigue

Compassion fatigue is often discussed in relation to burnout and secondary trauma. The International Classification of Diseases, or the ICD-11, characterizes burnout as an occupational phenomenon and defines it as chronic workplace stress that has not been managed and includes feeling depleted or exhausted, distancing or negative feelings towards one’s work, and reduced efficacy (WHO, 2019). Secondary trauma happens when a helping professional is exposed to the traumatic events of their clients or patients and then the helping professional begins to take on those experiences in a way that mimics trauma symptoms within their own life, even without having directly experienced the traumatic event (Marković & Živanović, 2022).

Professionals in the helping fields, similar to compassion fatigue, also experience higher levels of burnout and secondary traumatic stress (Parry et al., 2023). Substance abuse professionals experience a wide variety of secondary trauma from their clients and experience negative consequences at a higher rate (B. Bride & Walls, 2006). Factors contributing to compassion fatigue include low levels of support and decreased confidence (Turkington et al., 2023). The negative effects associated with compassion fatigue involve a lack of communication, professional errors, negative attitudes, and higher turnover rates (Cetrano et al., 2017). There is a strong association between the work environment and negative effects on professionals as well (Cetrano et al., 2017).

Compassion Satisfaction

Contrary to compassion fatigue is compassion satisfaction. Compassion satisfaction is the fulfillment that professionals get from being able to provide positively for others through their work (Saleem & Hawamdeh, 2023). Mental health professionals are more susceptible to negative consequences such as burnout and secondary traumatic stress, but they also experience high levels of compassion satisfaction (Aminihajibashi et al., 2024). One study found that counselors with personal trauma often had higher rates of compassion satisfaction (Brown et al., 2022). Contradictory research has emerged showing that having higher ACE scores results in less compassion satisfaction. More research is needed to account for the disparities between studies (Brown et al., 2022).

Burnout

Human services and addiction treatment professionals are exposed to a plethora of workplace stressors due to the high demanding nature of their work (Gutierrez et al., 2019). The high demands combined with worker exhaustion leads to a high rate of burnout amongst substance use professionals working in human services (Gutierrez et al., 2019). Professionals in the substance use field often possess deep emotional connections with clients, raising the stakes of stress and demand for the professional (C. B. Oser et al., 2013). One study completed by Vorkapic and Mustapic found that substance use professionals face the highest levels of burn out among human services providers (Gutierrez et al., 2019). A study completed by Fentem and associates found similar results to the previous studies related to burnout (2023). The study suggests that improvements in organizational worker support may be the key to addressing challenges that affect both professionals and clients (Fentem et al., 2023).

Perceived Social Support: Family and Significant Others

Perceived social support, especially from family and significant others, is a vital determinant of psychological and physical well-being. Recent studies highlight that family members, including parents and siblings, provide a primary source of emotional support that enhances coping mechanisms during stress. D’Angelo and colleagues (2022) found that family support is associated with better mental health outcomes and lower levels of perceived stress among young adults facing major life transitions. Perceived availability of support from family members can foster feelings of security and reduce the negative effects of anxiety and depression (Barrera et al., 2020). Family support appears to act as a buffer against adversity, enabling individuals to navigate challenges with greater resilience and emotional stability (Hare et al., 2021). This highlights the importance of the quality, not just the quantity, of family support in shaping psychological well-being.

Similarly, recent studies underscore the significance of social support from significant others, such as romantic partners and close friends, in enhancing mental health outcomes. Perceived support from social relationships is closely linked to improved emotional regulation and overall life satisfaction. Zhang and associates (2023) demonstrated that support from significant others contributes to greater relationship satisfaction and reduces the risk of mental health issues such as anxiety and depression. The perception that a romantic partner or close friend is available for emotional and practical assistance can buffer the negative effects of stress and promote adaptive coping strategies (Hughes et al., 2022). The positive effects of perceived social support from significant others extend to physical health, as individuals with strong social support networks tend to have lower blood pressure and better immune function (Gunn et al., 2020). These findings emphasize that the perception of supportive and responsive relationships with significant others plays a crucial role in both psychological and physical well-being.

Work Engagement

Work engagement is defined as the enthusiastic interest and immersion in one’s work where professionals are excited and engaged in their practice (Rollins et al., 2021). Work engagement is largely impacted by the organizational climate as well as leadership in the organization, especially in mental health and rehabilitation settings (Beitel et al., 2018; Rollins et al., 2021). Aspects of strong work engagement include being in a person-centered work environment that has strong management skills, as well as opportunities for professional development and self-care (Rollins et al., 2021). A work environment that values its professionals and is human-focused should foster strong work engagement (Rollins et al., 2021). Beitel and associates (2018) determined that strong work engagement decreases negative influences such as burnout and compassion fatigue.

Organizational Factors

Adequate leadership support, such as specific leadership styles like a transformational leadership style, a servant leadership style, or a trauma informed leadership style can promote the type of support that staff need for job satisfaction and reduced burnout which may influence efficacy in helping clients, dedication, and retention (Adams et al., 2025; Chen et al., 2022; Choy-Brown et al., 2020; Demeke et al., 2024; Kelly & Hearld, 2020; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2018).

The authors of this study hypothesized that the staff in recovery school settings are at high risk for negative impacts to professional quality of life (i.e., compassion fatigue, burnout, and STS), which can influence staff work engagement. Moreover, staff perceived social support is thought to be associated with their work engagement and professional quality of life factors. Previous studies have shown the association between job satisfaction and commitment to work in human services staff (Akingbola & van den Berg, 2019; Lizano, 2021) and to compassion fatigue, burnout, perceived stress, and turnover (Salloum et al., 2015; Weiss Dagan et al., 2016). Human services organizations environments that promote staff engagement tend to have greater staff retention and have staff who provide greater quality of care services thereby demonstrating the importance of examining the implications of study results on the factors in this study (Esaki et al., 2023; Steinheider et al., 2019).

Methods

Participants

Twenty RHS were identified through the Association of RHS (n.d.) website. Of the 20 contacted, one responded by email that they were closed (The Recovery High School Program at The Providence Center closed August 2023). All adult RHS staff, aged 18 and older, who were working in roles that required working directly with the adolescent students were eligible to participate in this study. Sample characteristics included age, gender (1=Male, 2=Female, 3=Non-binary/third gender) sexual orientation (1=Heterosexual or straight, 2=Lesbian, 3= Queer, 4=Pan-sexual), and marital status (1=Single/never married, 2=Married, 3=Living with partner, 4=Divorced). Also staff education level (1=, household income (ranging from $20,000 to $150,000 or more), residence location (1=Urban or city, 2=Suburban, 3=Rural), state, employment status (1=Full-time, 2=Part-time), time employed at the RHS (1=Less than one year, 2=one to four years, 3= five or more years), health insurance (1=No, 2=Yes), health insurance (1=No, 2=Yes) and type (1=Commercial through employer,2=Marketplace), and job role at the RHS (1=Peer recovery counselor, 2=Social worker, 3=Counselor, 4=Other). Participants were able to explain their role if they did not identify based on the aforementioned roles. Also, they were asked to identify if they were licensed (1=No, 2=Yes), were in recovery (1=No, 2=Yes), and if in recovery, indicate if they experienced any relapses since the RHS job role commenced.

Procedures

This study was approved by the authors university board. Primary data was collected by Qualtrics survey which included informed consent, sociodemographic questions, and three measures, namely the Adverse Childhood Experiences questionnaire, Professional Quality of Life measure version 5, The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support, and The Utrecht Work Engagement Scale. Behavioral health staff at 42 Recovery High Schools across the U.S. were outreached for recruitment via email and word of mouth snowball sampling from Recovery High School behavioral health staff. Researchers referenced a list of RHS from the Association of Recovery High Schools (n.d.) website. Researchers will send a flier by email to all 42 Recovery High Schools in the US and request distribution to behavioral health staff. The list of RHS was divided in half between the two authors who made phone calls to their assigned list of RHS. Phone calls were made in an attempt to identify a contact person, such as an administrator or other person in authority, that can approve circulation of a study flyer. Once this person was identified, and their email addresses were obtained, they were emailed a recruitment flyer.

There were three rounds of recruiting, that included a phone call and email to the identified RHS contact person. The recruitment period first took place March 2024, followed by a second round of recruitment outreach completed May 2024, and a final round of recruitment outreach was conducted September 2024.

Measures

Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE)

The ACE questionnaire for adults is an 11-item questionnaire designed to capture a persons childhood trauma experiences prior to the age of 18 (Felitti et al., 1998). Participants were to cumulatively indicate the items that they identify with in the 11-item list of questions in the measure. ACE example questions were: Did you lose a parent through divorce, abandonment, death, or other reason and did you live with anyone who has gone to jail or prison (Felitti et al., 1998). The larger the score (four or higher) suggests the greater likelihood of negative health related impacts associated with the identified childhood trauma. This measure has been shown to have good test-retest reliability with a reported weighted Cohen Kappa of .52 to .72 (Dube et al., 2004), which was affirmed to have acceptable reliability, with internal reliability ranging from .78 to .86 (Dobson et al., 2021).

The Professional Quality of Life Scale

The Professional Quality of Life scale, version 5 (ProQOL) is a freely available 30 item Likert scale measure consisting of three subscales measuring compassion satisfaction (CS) and compassion fatigue, which compassion fatigue is defined as burnout and secondary traumatic stress (STS). The Likert scale is 5 points (1=Never, 2=Rare, 3=Sometimes, 4=Often, 5=Very often).

This measure consists of three subscales. One subscale is named the CS subscale. CS is defined as a person’s personal satisfaction with their work (Stamm, 2010). CF is also measured in this scale, which consists of subscales of burnout and STS. Burnout is described as frustration, anger, and exhaustion whereas STS is described as negative feelings and trauma associated with work related experiences (Stamm, 2010). Example statements include: “I am happy,” from the Burnout subscale, “I am preoccupied with more than one person I help,” from the STS subscale, and “I get satisfaction from being able to help people” from the CS subscale (Stamm, 2009, pp. 29–30).

Score interpretation of ProQOL varies according to the subscale. CS scores below 23 indicate problems or measured factors experienced in some other aspects of participants lives. The higher the score the more positive the CS. The CS subscale reliability has been found to be 0.88 (Stamm, 2010). Concerning burnout, scores that are below 23 suggest positivity about the work whereas 43 indicates that they may be worried, have a cause for concern, and possibly experience feelings of ineffectiveness. Burnout subscale reliability is 0.75. STS scores explain work related trauma, that has been called vicarious trauma (Stamm, 2010). Scores over 43 suggest a need to examine causes that may explain this elevated score since Stamm (2010) says this score does not necessarily mean there is a problem. STS reliability is shown as 0.81 (Stamm, 2010).

The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support

This scale uses three subscales subjectively measures participant perceptions of social support from family, friends, and significant others. There are 12 Likert scaled items on a seven-point scale (i.e. 0=Very strongly disagree to 7=Very strongly agree). Mean scale scores for each subscale are calculated by summing the subscale items and diving the sum by four. All scale items are summed and divided by 12. Subscale and overall scale scores are then interpreted with the following meaning: 1 to 2.9 suggests low support, 3 to 5 explains moderate support, and high support is a mean of 5.1 to 7 (Zimet et al., 1988). Example scale items per each subscale, the Family, Friends, and Significant Other subscales were: "My family really tries to help me, " “There is a special person who is around when I am in need,” and “My friends really try to help me.”

The 12-item scale has been found to have acceptable Cronbach alpha, .97, and across each of the Family, Friends, and Significant Other subscales respectively were .91, .89, and .91 (Canty-Mitchell & Zimet, 2000; Clara et al., 2003). Discriminant validity has been found for the Family subscale (Canty-Mitchell & Zimet, 2000). Friend support was not measured in this study due to data constraints.

The Utrecht Work Engagement Scale

There are three versions of the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale. The used in this study is the 17-item measure, which we selected to use due to this being the original scale and it having six vigor items, five dedication items, six absorption items, the other versions are brief with less items measuring each subscale. It consists of three subscales that measure vigor using six items with Cronbach alpha of 0.82, (i.e.., “At my work I feel bursting with energy”), five items measuring dedication with Cronbach alpha of 0.89 (i.e.., “I feel enthusiastic about my job, my job inspires me”), and six items that measure burnout that have been shown to have a Cronbach alpha of 0.83 (i.e. “Time flies when I’m working, I feel happy when I’m working intensely”; Baker & Schaufeli, 2004, pp. 5–6). There is a six-point Likert scale (1=Never, 2=Almost never, 3=Rarely (once or less monthly), 4=Sometimes (a few times monthly), 5=Often (once weekly), 6=Very often (a few times weekly), 7=Always (daily). Higher scores suggest better energy, resilience, and focus concerning work.

Data Analysis

Some ProQOL items (ie., 1, 4, 15, 17, and 29) were reverse coded (Stamm, 2009). Distribution of continuous data was checked, and the distribution was normal. Missing cases were imputed, and all measures subscales were computed. We utilized descriptive analysis and conducted bivariate analyses using Spearman’s rho correlation. SPSS version 29 was used to analyze the data and determine if there are any statistically significant differences (alpha =.05).

Results

Descriptive Analysis

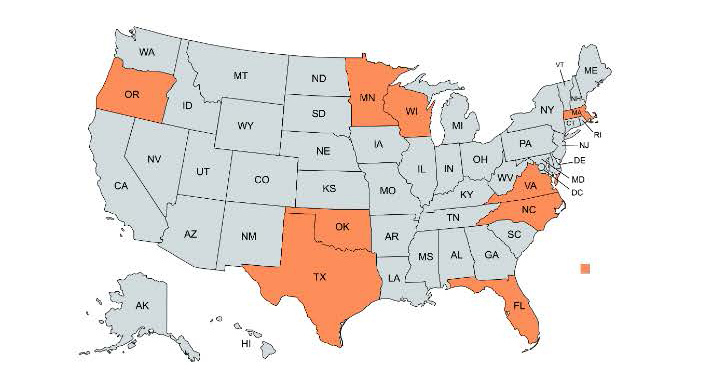

Survey results were comprised of 22 participants from nine states (Figure 1). The sample (Table 1) consisted of mostly females (n=15, 68.2%), ages ranging from 27 to 63 years old, who had a mean age of 27.14 (SD=10.13) Most identified as White (n=16, 72.7%) followed by Black (n=2, 9.1%), heterosexual (n=17, 77.3%), married (n=11, 50.0%) or single or never married (n=5, 22.7%). Most had a professional degree (n=10, 45.5%) followed by some college (n=6, 27.3%), and finally, a four-year degree (n=4, 18.2%). Household income median was $80,000-$89,999 (IQR=$60,000-$69,000, $100,000-$149,999). A full-time employment status was endorsed by most (n=21, 95.5%) and they mostly reported one to four years employment (n=9, 40.9%) at the school followed by more than 5 years (n=8, 36.4%). They were also mostly located in a suburban (n=11, 50.5%) area followed by urban or city areas (n=9, 40.9%). Most participants were not social workers (n=1) or counselors (n=6) and instead reported other roles (n=11, 50.0%) such as teacher, dean of students, executive director or director, mental and behavioral health specialist, program director/school counselor, or a recovery coach.

ACE results showed that six of the 22 participants indicated that they had no exposure to childhood trauma. Ten experienced four or more traumas which suggested a high risk for health and social problems, such as mental illness and chronic physical health conditions. More specifically, out of the 22 people sampled, most staff (n=10) lived with someone who had a problem with drinking or doing drugs before age 18. Many (n=10) experienced a parent or adult swearing with them or putting them down, insulting them followed by nine sampled experienced being hit, beat, kicked, or physically hurt in any way by an adult and eight experienced living with someone who was depressed, mentally ill, or attempted suicide.

Univariate Analyses

Univariate results are presented in Table 2. RHS staff professional quality of life results showed the staff experienced moderate to high levels of CS (Mdn=41.50, IQR=36-45). Burnout scores were found to be on the lower end (Mdn=23.00, IQR=20.75-27.50) and STS results being more moderate in this sample of staff (Mdn=22.50, IQR=17-26.50).

The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support subscales showed high perceived support concerning significant others (Mdn=6.50, IQR=6.25-7) and high perceived support concerning family support (Mdn=5.38, IQR=4.69-6.81). Most identified that “special person” as their spouse/partner (n=14).

The Utrecht Work Engagement Scale sample mean across subscales results showed that staff agreed with survey questions pertaining to vigor =5.33, SD=.742), dedication =5.65, SD=.687), and absorption =4.95, SD=.702). These results suggest the average staffperson has high work engagement.

Bivariate Analyses

Using Spearman’s rho, we examined if there is there an association between RHS staff professional quality of life, perceived social support, and work engagement. Results (Table 3) showed a statistically significant moderate positive relationship between sample CS and dedication (rs(20)=.486, p<.05), showing that CS explains 24% of the variance in dedication.

These results revealed that better CS indicated better work dedication. However, we found no significant results pertaining to staff professional quality of life, ie. Compassion satisfaction, burnout, and secondary traumatic stress, and family support, significant other support, or staff quality of life and their work engagement, vigor, and absorption.

Discussion

This study revealed valuable information regarding staff in RHS. We examined RHS staff who worked directly with adolescent students. Participants were from nine different states across the country, allowing for an immensely geographically diverse sample. Given previous studies showing that staff retention and burnout may impact adolescent substance use and treatment retention, we examined RHS staff specifically due to the specialized nature of these school settings.

Previous research showed the relationship between staff turnover and adolescent substance use and sobriety and the association of facility level barriers relevant to staff burnout and staff retention (Acevedo et al., 2020). Staff in these settings are uniquely oriented and trained to work with adolescents in recovery from a SUD whereas providers who work with adolescents with a SUD in traditional school settings may not be as uniquely prepared to address the level of need these adolescents can have, which suggested that these staff may not have similar experiences as providers and staff of these settings (Viverette et al., 2024). Their niche focus, combined with clinical regular involvement, could be critical hence the need for this study.

Results showed a positive correlation between CS and dedication. The higher level of dedication that staff had to their job resulted in higher levels of CS in the workplace. Previous research revealed that staff often experience high levels of CS from their work (Aminihajibashi et al., 2024; Jennings & Min, 2023). This may be explained by RHS students negative experiences that are heightened due to their experiences with their educational environments, substance use treatment, and sobriety (Bowie-Viverette et al., 2024; Viverette et al., 2020) and the role of leadership style, workplace workload and job resources, such as supervisory support (Landrum et al., 2012; Singh et al., 2020). CS acts as a protective factor for staff against potential STS and burnout (Saleem & Hawamdeh, 2023). The findings of the previous studies parallel the findings of this study and suggest that CS should be prioritized for staff in order to maximize staff quality of life. The study findings further affirm the previous literature in the field regarding the interaction between satisfaction and burnout experienced by professionals.

Another finding of the study is that almost half of the participants identified with high levels of ACE. Previous studies have found that higher levels of adversity can be linked to lower levels of satisfaction, but this study revealed both high levels of adversity and high levels of compassion satisfaction (Brown et al., 2022).

Overall, this study contributes to the knowledge base of RHS staff. Based on these results, RHS sampled staff are experiencing satisfaction, dedication, and support in their work despite working in this specialized setting. The staff in recovery schools may able offset STS, and burnout, and have better work dedication due to the higher compassion satisfaction.

Implications

This study has implications for human services staff and RHS leadership working with adolescent students with SUD related needs. Human services staff tend to be at increased risk for stress and burnout (Stacks & Stein, 2014). Therefore, staff awareness of their own risk factors to STS and identifying protective factors for staff against STS is paramount since staff working in human services settings may have a high prevalence of traumatic experience themselves (Esaki & Larkin, 2013). Staff may find it informative to be strategic about training and personal self-care behaviors that might influence their professional quality of life, perceived support, and work engagement. Raised awareness among staff means attending training and engaging in self-care at the individual level as well as organizational opportunities of support (Esaki & Larkin, 2013). There has been a proliferation of self-care training programs since Nelson’s 2018 study suggested self-care trainings were in limited supply. Staff deliberately engaging in these self-care training programs is suggested, which can be promoted by their leadership.

A trauma informed leadership approach is suggested for RHS leaders. The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (2018) outlined that trauma informed organizations meet four criteria: a) “Realize the widespread impact of trauma; b) recognize the signs and symptoms of trauma, c) respond by integrating the knowledge of trauma into practice, and d) actively resist retraumatization.” Therefore, RHS organizational leadership are suggested to facilitate work environments that are conducive to worker engagement so as to advance worker retention and effectiveness (Steinheider et al., 2019), fostering staff resilience and wellbeing, promote worker satisfaction, all while reducing retraumatization of staff (Hambrick et al., 2018). Previous research has described that leadership can be positively impactful, at the individual staff level, meaning staff being supported in their own self-care, of burnout, retention and turnout, mental health, such as depression, anxiety, and stress by limiting burdensome administrative tasks that are not directly influential to adolescents (Acevedo et al., 2020), implementing mindfulness programs during staff scheduled breaks, and overall education of staff (Cohen et al., 2023). At the organizational level leadership are suggested to note that policies, procedures, and systems that address job crafting, peer support, and workload, and an organizational trauma informed approach can have positive outcomes for staff (Cohen et al., 2023; Esaki & Larkin, 2013; Mahon & Sharek, 2023).

Limitations and Future Research

The limitations of this study include having a small convenience sample, making it difficult to generalize findings outside of the sample population. We reached out to 42 RHS and not all invited RHS staff participated. We had low response rates which also affected sample size and generalizability. The population also identified with suburban and urban areas, and the sample population did not include participants from rural settings. This study did not examine organizational factors that may impact the studied measures nor explore these phenomena.

Findings showed the need for further examination of protective and supportive factors for staff in RHS. Staff ACE findings need to be further explored to determine a more solid foundation for the intersectionality of ACE and CS and substance use history and CS among staff in this specialized school setting. Future research should be conducted with more states and with more RHS participants using more robust sampling methods and parametric testing and larger, more diverse sample populations in order to generalize results; however, since RHS tend to be small population schools this may not be feasible (Moberg et al., 2015). Future research should also examine other influential factors that may impact compassion satisfaction as well as secondary traumatic stress and burnout, such as the effects of leadership. Further examination should examine organizational factors that may affect studied measures and also be dedicated to the intersectionality of organizational protective factors with STS and burnout specifically. Use of qualitative studies can allow for participants in recovery school settings to fully express their experiences associated with study results.

Conclusion

This study delved into the varying components of professional quality of life and work engagement for RHS staff. Literature shows that there are both risk and protective factors for professionals who are working in more challenging environments with kids and adolescents. Compassion fatigue is a common term that comes up around the topics of mental health and recovery school workers. This study showed that almost all of the participants had experienced at least one ACE and almost half of the participants had experienced four or more ACE. Overall, staff experienced moderate to high levels of compassion satisfaction in their work while burnout was not a common theme in the sample. STS was measured as moderate among the staff. A majority of the staff indicated they had high levels of support from family and spouses. The result of the study confirmed that having higher compassion satisfaction is associated with lower levels of secondary traumatic stress and higher dedication and vigor in their work. However, higher levels of secondary traumatic stress were associated with higher levels of burnout as well among the staff. The results of this study confirm a correlation between secondary traumatic stress and burnout, as well as a negative correlation between compassion satisfaction and burnout.

Acknowledgements

I thank Graduate Research Assistant Cheyenne Williams for writing and editing assistance.

Conflict of Interest Statement

All authors certify that they have no affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest or non-financial interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript. We consulted the IRB of Texas State University who approved the study. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.