I. Introduction

The United States child support program aims to improve children’s economic well-being by transferring financial resources from parents living outside of the home to children. When paid, child support can be an important resource for custodial parent families and children; however, most custodial parents (CPs) owed child support receive less than full payments (Grall, 2020). The child support program particularly struggles to facilitate collections from noncustodial parents (NCPs) with limited financial resources and who are unemployed or underemployed (Berger et al., 2021; Cancian et al., 2021; Hodges et al., 2020; Mincy et al., 2014). For decades, predominant narratives cast nonpaying NCPs as “deadbeats”, unwilling to support their children (Battle, 2018; Meyer & Kim, 2021; Mincy & Sorensen, 1998); traditional child support enforcement tools—such as suspending or threatening to suspend licenses, seizing assets, and judicial enforcement—reflect this notion and take a punitive approach to encouraging compliance. However, many NCPs have limited ability to pay formal support regularly (Bartfeld & Meyer, 2003; Cancian et al., 2021; Hodges et al., 2020; Pate, 2016; Sorensen & Zibman, 2001; Turetsky & Waller, 2020), rendering sanction-based approaches less than effective.

In recent years, policymakers, child support leaders, and practitioners have suggested that connecting NCPs who experience employment-related barriers to supportive services is worth considering (Hahn et al., 2018; Office of Child Support Enforcement, 2022; Turetsky, 2010). While the notion that child support agencies (CSAs) could take an alternative approach to serving families when NCPs are behind on support has gained momentum in recent years, the state of the field remains in considerable flux. Though the federal Office of Child Support Services “believe[s] the option to implement noncustodial parent employment services is a good strategy to increase participation in the workforce, improve compliance with court-ordered child support payments, and provide low-income Americans with a path out of poverty” (Office of Child Support Enforcement, 2022), federal funding for employment services programs is limited, and whether and how states implement employment-related services for NCPs varies across and within states (Office of Child Support Enforcement, 2021). Further, even when funding is available and policy directives are clear, shifting organizational culture and processes to facilitate new ways of working takes time and comes with an array of hurdles for agencies to navigate. CSAs experience further challenges for working in new ways due to the child support program’s historical narrow focus on collections and enforcement and often adversarial relationship with NCPs (Noyes et al., 2018; Vogel, Dennis, et al., 2022).

Given this rapidly changing landscape, this study aimed to explore current perceptions and practices among CSAs for connecting NCPs to employment and other supportive services, as well as future plans. Through surveys of Wisconsin child support agency directors, and in-depth interviews with local agency directors and staff, this study explores CSA director perceptions about the current and future role of CSAs in this realm; perceptions about NCP service needs, accessibility, and gaps; and views on impediments to CSAs serving in a “connector” role.

A. Background

1. Barriers to Child Support Compliance

Inability to pay child support is a crucial problem for child support compliance (Bartfeld & Meyer, 2003; Cancian et al., 2021; Hodges et al., 2020; Mincy & Sorensen, 1998; Pate, 2016; Sorensen et al., 2007; Sorensen & Zibman, 2001; Turetsky & Waller, 2020). Unemployment, underemployment, and low earnings make it difficult for some NCPs to pay the support that they owe while meeting their own basic needs (Cancian et al., 2021; Eldred & Takayesu, 2013). A number of barriers to work directly relate to the type of jobs available to NCPs and their earning potential; for example, low levels of education and lack of work experience are significant barriers to work for many NCPs (Berger et al., 2021; Cancian et al., 2018; Noyes et al., 2018; Vogel, 2020), as is having a criminal record (Berger et al., 2021; Cancian et al., 2019, 2021; Eldred & Takayesu, 2013; Noyes et al., 2018; Vogel, 2020). In addition to factors directly related to job availability, many NCPs experience other barriers that can affect their ability to obtain and keep work, including transportation barriers, criminal records, caregiving responsibilities, housing instability, substance use issues, and physical and mental health difficulties; further, prior research has emphasized for many NCPs who experience barriers to work, barriers often co-occur (Berger et al., 2021; Noyes et al., 2018; Vogel, 2020). Many barriers of these are beyond the immediate purview of the CSA, suggesting that a collaborative approach involving an array of service providers is likely necessary for addressing them.

2. Child Support Agencies and Services to Address Barriers

In recognition that new approaches might yield better outcomes for NCPs with limited ability to pay child support, several recent efforts have sought to connect NCPs to services aimed at addressing employment barriers. Though nearly two-thirds states have efforts underway to support NCP connections to employment resources (Office of Child Support Enforcement, 2022), programs are often small in scale and limited in scope and populations served, due to funding challenges, including limitations on using federal child support resources to fund employment services absent a waiver to do so (Landers, 2020). Findings from evaluations of demonstration projects aiming to improve the employment outcomes of NCPs, as well as other research with CSAs, suggest some practitioners find connecting NCPs to employment resources and other supports as potentially beneficial for helping NCPs address barriers to work and compliance (Landers, 2020; Noyes et al., 2018; Pratt & Hahn, 2021; Vogel, 2021; Vogel, Dennis, et al., 2022; Vogel, Pate, et al., 2022). These evaluations also highlight factors that support CSA efforts to implement such programs, including strong partnerships with community providers; regular and thoughtful communication across, and co-location with, partners; overcoming mistrust among NCPs and resistance to new ways of working among staff; and developing service strategies to address multiple and complex NCP barriers to work and paying child support (Noyes et al., 2018; Pratt & Hahn, 2021).

3. Exploring New Frontiers: Moving from Policy to Practice

The problem of noncompliance with child support obligations is well-documented in the research literature, and the child support policy environment has begun a definitive shift towards reconsidering approaches to serving NCPs with barriers to work and paying. And yet, missing from the existing literature is the perspective of the people responsible for translating policy goals and directives into practice – the leaders and staff of local CSAs who interact directly with families and shape their experiences. Organizational leaders are crucial for shaping local goals, priorities, and processes (Moullin et al., 2018). The role leaders believe their CSAs should play in connecting NCPs to resources, therefore, will likely matter for how such efforts unfold. CSA leader perspectives on what serving in a “connector” role means for their organization, their priorities related to serving in this role in the future, and how these goals align with future practice have not yet been systematically examined, representing an important gap in the literature. Further, understanding CSA leader perceptions of what needs the population of NCPs served by their organization has, the resources available locally to meet these needs, and the challenges they face in connecting NCPs to resources, can potentially help policymakers develop guidance and resources to support local implementation. This study aims to address these gaps, by exploring CSA needs, resources, constraints, and current practices in support of future efforts.

II. Methodology

This study uses an exploratory, sequential mixed-methods design (Teddlie & Tashakkori, 2009) to explore the following research questions:

-

What role do CSA leaders believe that CSAs should play in serving NCPs with employment barriers? How does this vision align with current practice?

-

What services do CSA leaders perceive NCPs need to address employment barriers? What factors impede NCP access to services?

-

What factors can make it difficult for CSAs to serve in a “connector” role?

-

How does serving in a “connector” role fit into CSA’s future plans? What policies, guidance, or resources could help CSAs to work in this way?

In the study’s first phase, the research team conducted interviews with CSA directors and staff, to yield a foundational understanding of how CSAs work with NCPs having issues with employment, and how and where they connect NCPs for support. Findings informed the study’s second phase: a survey of all Wisconsin CSA directors. All study activities were approved and overseen by the study team’s university Institutional Review Board and informed consent was obtained for all participants in both study phases.

A. Interview Sample, Data Collection, and Analysis

In the study’s first (interview) phase, the study team interviewed directors and frontline CSA staff—including child support case managers and supervisors—in 5 of Wisconsin’s 71 counties. Counties were identified and selected based on three criteria to maximize diversity in CSA experiences and community contexts: size (small, medium, and large size counties), geography (one county from each of Wisconsin’s five regions), and programmatic offerings available specifically for child support NCPs within the county (counties with and without these offerings). In total, 15 participants (5 directors and 10 frontline staff) completed interviews, which lasted an average of 75 minutes and were guided using a semi-structured interview protocol. Topics included CSA staffing and organization; perceptions of NCP employment barriers and service needs; views on the CSA’s role in serving NCPs with barriers; practices and perceptions related to connecting NCPs to services; service providers and gaps; and support or guidance desired. Data were coded in NVivo12, analyzed thematically, and used to develop and refine survey topics, questions, and response categories.

B. Survey Sample, Data Collection, and Analysis

When the interview phase of the study was complete, the study team fielded a Qualtrics survey. The survey topics and structure mirrored those of the interviews. The survey was initially developed drawing on the Child Support Noncustodial Parent Employment Demonstration (CSPED) evaluation’s staff survey instrument (Noyes et al., 2018)- a web-based staff survey used to collect data about collaborative efforts between CSA staff and other service providers for providing program services to NCPs having difficulty with work and paying – and refined based on learnings from the interviews conducted in the study’s first phase.

The sample for the survey included the directors from each of Wisconsin’s 71 CSAs.[1] Recruitment began with an advance email providing notification of the study, sent on behalf of the study’s sponsor to all CSA directors, followed by an invitation email from the study team. Non-responders received up to three reminder emails and a phone call over five weeks. Directors completed surveys on behalf of 59 county CSAs; two additional surveys were partially completed, for an 85.9% response rate.[2]

Close-ended survey data were cleaned and analyzed in STATA 16, which was used to generate descriptive statistics, and open-text responses were analyzed in Excel. For questions that included a list of response options along with an “other, specify” text field, where possible and appropriate, the open-text responses were back-coded into one of the existing survey response options. For fully open-text survey questions, responses were thematically grouped in Excel and when they provided relevant context for other study findings, they were presented alongside interview data, especially when they expressed a commonly held belief.

III. Results

A. CSA Operational Contexts

How CSA staff are organized has potential implications for who within a CSA might become aware of an NCP falling behind on support, and staff caseload sizes can affect staff capacity to respond to learning of an NCP falling behind with personalized follow-up (Vogel, 2021). On surveys, directors were asked whether their caseworkers manage cases start-to-finish or specialize by function (Table 1). Most directors (70%) reported that their agency’s caseworkers manage cases start-to-finish, with 30% specializing by function. In counties that manage cases start-to-finish, directors shared in interviews that cases are typically allocated alphabetically to caseworkers, whereas in counties that specialize, staff are generally organized by function, such as enforcement, paternity, order establishment, or interstate coordination. On average, directors reported that their CSA staff carry 728 cases on their caseloads, with a substantial range in caseload size across counties. Directors in counties where staff work cases start-to-finish reported average caseloads of 428 per caseworker, whereas directors in counties where staff specialize reported 997 cases per caseworker. In just under half (45.9%) of counties, directors reported carrying their own caseload, averaging 212 cases. Directors themselves had different levels of experience, ranging from almost three decades to having just joined the agency.

B. The CSAs Role in Connecting NCPs to Services

1. Perceptions of What Should be Expected of CSAs

Child support agency leaders set the tone within their agencies and establish departmental priorities. How they feel about the role their CSA should play in helping NCPs with employment barriers is an important context for understanding current and future practices, particularly given that CSAs have taken a narrow, enforcement-oriented approach in the past. Further, absent a clear mandate or funding from federal or state authorities, the specifics of what this “connector” role should entail might reasonably be expected to differ across directors and CSAs. To gauge director views on the role the CSA should play in serving NCPs with employment barriers, the survey asked directors a series of three yes-or-no questions: whether directors believe CSAs should be expected to: (1) provide employment services directly to NCPs who are not working; (2) to refer them to local employment providers; and (3) to refer them to other supportive services beyond employment services, such as services for mental health, substance use, parenting supports, or access and visitation. Survey findings indicate that directors broadly support the notion that CSAs should be expected to play a “connector” role. 92% reported that CSAs should be expected to refer NCPs to employment services; most, but fewer, (79%) reported that CSAs should be expected to refer NCPs to other supportive services. In contrast, only 28% of directors felt CSAs should be expected to directly provide employment services.

Data gathered in interviews provides insight into the value CSAs see in this “connector” role. In interviews, directors said that such brokering by CSAs “makes sense” and is a “part of our job to some extent” because employment assistance can help NCPs subject earn income to pay their child support obligations. Thus, some see this more supportive role for CSAs as both sensible and strategic, because doing so helps CSAs become more “successful” in collecting child support, whereas a more traditional punitive approach “usually doesn’t work,” as two directors noted in interviews. One staff member observed that the task of connecting “has to start on the child support side,” rather than on the part of other providers, because the CSA knows which NCPs have fallen behind on their obligations and is best situated to connect NCPs to employment services. In interviews, directors and staff who felt that it was not appropriate for CSA staff to provide employment services directly cited limited time and staff available to manage caseloads already and a lack of capacity for this additional responsibility. As a case manager described, “I don’t have a lot of time to be doing research for people … [M]y job is not to help them find work, as much as I want to… That’s why I refer them to the jobs programs.” Beyond capacity issues, some staff members in interviews also shared concerns about lack of expertise in this domain relative to other organizations that focus specifically on employment. As a director stated, “We’re not going to be specialists in all areas. But we certainly can link people to specialists. As long as we can continue exposure, we can at least give our clients an option.”

Interviews also provided insight into why a smaller share of directors think CSAs should be expected to make referrals to other supportive services than to employment services. In interviews and on open-text items on surveys, some directors shared that they consider non-employment referrals outside of the CSA’s purview. Some believe “establish[ing] relationships with outside services for mental health, the DMV, etc…. is not the CSA’s job” while others are more concerned about “crossing boundaries” and the “fine line of what’s within the CSA’s scope.” One case manager alluded to playing this broader role as a risk for compromising the CSA’s “neutrality”, stating, “If we’re making that referral to send them somewhere, then we’re saying, “this is the best place for you”… I think that that could come back to bite us in the end if we’re giving those sorts of referrals to people and it didn’t work out for them.”

2. Current CSA Expectations for Making Connections

In order to understand how current CSA practices align with the broadly held perspective that CSAs should be expected to connect NCPs behind on their support to employment services or other supportive services, the survey asked about current CSA expectations and perceptions related to these referrals in current practice. First, the survey asked whether caseworkers within their agencies are expected to (1) take specific steps upon learning that an NCP has lost a job or (2) to determine next steps themselves. Then, the survey asked directors who held expectations for specific steps to indicate what those steps included, as a series of four yes-no items derived as likely to occur in the study’s interview phase. Fewer than half (41%) of directors reported that staff are expected to take specific steps. Among those with expectations, most (85%) answered “yes” to expecting that caseworkers share information with the NCP about employment service options for the NCP to follow up on; reaching out directly to the NCP for more information (76%); taking steps to include employment service participation in a court order (76%). A smaller majority (62%) answered “yes” to an expectation that caseworkers share information about the NCP to an employment provider for the provider to follow up on. To understand expectations related to referrals for other supportive services, the survey asked whether the agency expects caseworkers to make a referral if another supportive service need is identified, as a yes-no question, and how likely (regardless of agency expectations) director’s think it is that caseworkers will make referrals in these situations. Only 25% of directors reported that their agency expects caseworkers to make referrals to other types of services if a need is identified. Further, regardless of whether the agency has such expectations, only 26% of directors described it as “very” or “extremely” likely that caseworkers will make a referral under these conditions, with 34% answering “somewhat” likely, and the rest (40%) answering “not at all” or only “a little” likely.

C. Perceptions of Service Needs, Service Gaps, and Service Access

The types of places CSAs might refer NCPs for services depends on agency awareness of and perceptions related to NCP needs. In the study’s first (interview) phase, the research team asked directors about their perceptions of the kinds of issues that get in the way of finding and keeping work for the NCPs served by their agency. The survey then asked all directors their perceptions of the extent to which each of those factors are a problem among their CSA’s NCPs for finding or keeping a job, using a 5-point scale ranging from “not a problem at all” to “an extremely large problem” (Figure 1). Substance use issues, lack of desire to work, and having a criminal record emerged as the most commonly-reported barriers, with the majority of directors reporting these as “very” or “extremely” big issues. Directors and staff expanded upon the challenges presented by these barriers in interviews. With regards to criminal records, directors and staff described that many employers are reluctant to take a chance on someone with a criminal record, particularly for certain types of crimes and better-paying jobs. Interview participants also expanded upon reasons why NCPs might lack motivation to find or keep work, citing factors such as low-wage jobs; high child support order amounts relative to earnings resulting in some NCPs having very little money left to spend on their own basic needs; and high levels of child support arrears compounded by mounting interest making it hard for NCPs to “see a light at the end of that tunnel” and therefore choosing to give up on formal employment. Interview participants stressed that many NCPs experiencing such difficulties often have multiple barriers to work that are inter-related; for example, substance use issues can result in a driver’s license being taken away, which can result in transportation barriers to work.

The survey asked directors to share information about the types of employment services resources available to NCPs behind on their support in their local communities, and their perceptions of the accessibility of those services to NCPs. On average, directors reported on surveys that CSA staff within their agencies make referrals for employment services to four employment service provider programs. However, in interviews, an issue that surfaced repeatedly related to the availability of employment services providers in small counties, particularly in the northern region of the state. On surveys, nearly one-third (32%) of directors reported that they place their CSA’s staff refer NCPs for employment services most often is located outside of the county (particularly noteworthy given that nearly half of directors reported transportation issues as an employment barrier for their CSA’s NCPs in Figure 1). Only one-third of directors indicated that the place they refer NCPs most often for employment services is located along a public transit route (with 39% describing the partner as not along a public transit route and 30% unsure). In interviews, staff and directors noted that distance from employment options presents challenges for accessing these services and increases the likelihood that NCPs are not aware of them.

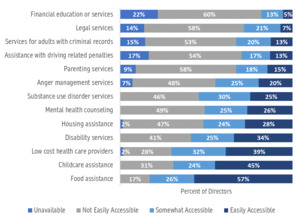

As shown in Figure 1 – and as identified in interviews by CSA directors and staff - issues beyond the realm of traditional employment services can create barriers to employment for NCPs. In order to understand what supportive service options are available, on surveys, directors were asked to assess the availability of other supportive services beyond those directly related to employment, accessible these services are for NCPs served by their CSA, using a five point scale ranging from “not at all easy” to “extremely easy,” with an option to indicate that the service category is not available in their area (Figure 2). Importantly, many of the services directors were most likely to assess as “unavailable” or “not easily accessible” negatively align with director reports of NCP barriers to work. For example, whereas Figure 1 shows that many directors perceive substance use, criminal history, and transportation issues as “very” or “extremely large” barriers to employment for NCPs (see Figure 1), legal services, services adults with criminal records or driving-related penalties, and substance use and mental health services were identified as not available or not easily accessible by nearly half or more of directors (in Figure 2).

D. Challenges for CSAs Acting as Connectors

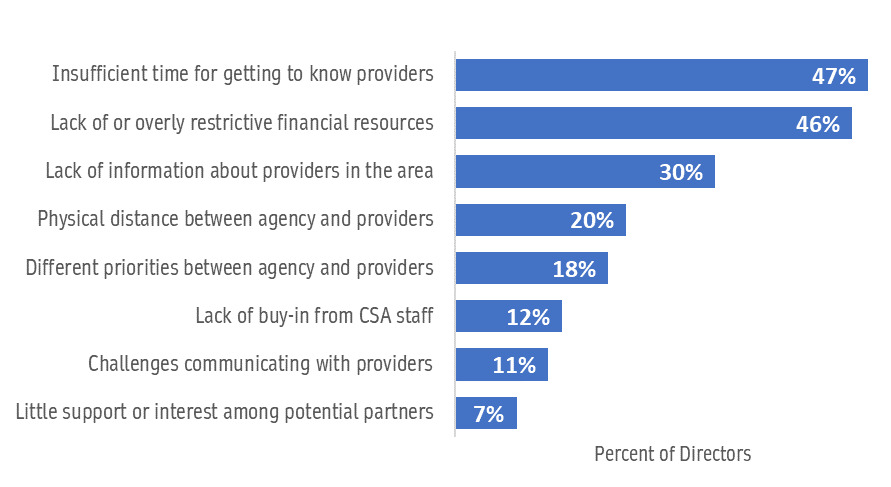

Though CSA directors broadly endorsed the notion that CSAs should be expected to serve in a “connector” role, and a goal of strengthening relationships that help them fulfill this role, directors and staff identified in interviews that an array of factors can impede CSAs from functioning as connectors to the extent that they aspire. A key challenge that emerged in interviews was the nature of collaboration itself. Directors and staff identified practical and historical factors that can make it difficult to collaborate with other service providers, even when they aspire to. The survey asked directors, using a five-point rating scale to indicate the extent to which each of these factors identified in interviews impeded their abilities to do so over the past year (Figure 3). The top barrier, lack of time for getting to know other providers, emerged in interviews as a key theme; child support agency leaders stressed that large caseload sizes limited time for building relationships with other community providers and learning about the resource landscape. Nearly half (46%) of directors reported “lack of financial resources, or restrictions on how my CSA can use financial resources” as limiting their collaborative efforts “a lot” or “a very great deal”, and nearly one-third (30%) cited lack of information about local providers.

Directors and staff noted that these collaboration challenges sometimes co-occur. For example, a caseworker described how infrequent communication with an employment services provider, staff turnover at both agencies, and pandemic-related office closures made it difficult to forge connections last year, with lack of time being the foremost barrier. Noted the caseworker:

It would be helpful to have one liaison [from the employment partner] that would come in and meet with us from time to time to just give us an update, or if we could work together to come up with new ideas. We could email, [but] the problem is, we don’t know who we’re emailing because the person we used to talk to is no longer there.

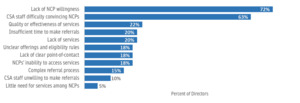

The survey also asked directors to share their perceptions of the kinds of factors that impede their CSA staff from making more referrals to employment service providers, derived from issues that arose as barriers during the interview phase of the study (Figure 4). Resoundingly, directors cited lack of willingness on the part of NCPs to engage in services as a key barrier for making referrals; directors described NCPs’ unwillingness to participate in services (72%) and staff difficulties convincing NCPs to engage in services (63%) as factors limiting the number of referrals made by their CSA’s case managers “a lot” or “a very great deal.”

Directors and staff expanded upon their perceptions of NCP willingness, and CSA staff difficulty convincing NCPs, in interviews. Directors and staff took one of two broad perspectives. Some felt that lack of motivation to work served as a strong impediment to willingness to engage in services; some felt that in the current economy, anyone who wanted to work could find a job. One director said, “From my experience, people who want to work, find a job and work and pay their obligations. And the ones that don’t, don’t.” Added a staff member:

My biggest problem is [employment programs] come to us, and they tell us to refer, refer, refer, but we know that the people we’re referring don’t want to work, and they’re not going to cooperate… I have never in all the nine years I’ve been here, I have not come across one person who legitimately wanted to work and could not find a job. If they want to work, they find work.

Other directors and staff expanded upon their perceptions of a more complex array of factors that might limit some NCPs’ motivation to participate in employment or employment-related services. Some directors and staff perceived that some NCPs believe that they cannot make enough money to meet their basic needs even with the help of an employment program, due to having a criminal record or after child support is withheld from a paycheck. They felt that for some NCPs, this perspective demotivated them from wanting help with finding a job or led to a preference to work for cash. One staff member added that NCPs with low incomes sometimes fear becoming ineligible for public benefits because of obtaining a better-paying job, as losing these benefits could negatively impact their overall well-being. Described the staff member:

Criminal backgrounds make it very difficult for some people to, you know, find jobs where they feel that they can make enough money to survive. That’s a complaint I hear quite often is just, you know, ‘I have a background, the only jobs I can get pay a little, and then you guys come in and take up to 60% of that.’ So that they just feel that it’s not worth their time if they’re not going to have any money to even live off from. And sometimes that job might be enough to bump them from getting certain benefits.

Additionally, directors and staff noted in interviews that some NCPs already have jobs, such as part-time work or self-employment. Though potentially inadequate for meeting their obligations, they perceived that some NCPs preferred to keep the jobs they had rather than participate in services to find a new job, feared losing that job as the result of program service participation requirement, or had limited availability for participating in services due to their work schedules.

Directors and staff also perceived that for many NCPs, feelings of pride—or conversely, of shame for receiving help—led them to prefer to seek employment on their own, rather than with the help of a service provider. As a staff member described, “A lot of the times when I mention our job programs and resources, I’ll get responses like, ‘Well, I think I have some things that are coming down the line. I’ll figure it out myself.’ I wonder sometimes if it’s an element of pride.” Another staff member described how competing obligations and feelings of pride, among other factors, can intersect to create barriers to engagement:

I do try to stress to people that with child support orders, it’s different than other bills. You could potentially go to jail, if you’re not following your order. It’s not like a normal bill. I also think that there’s a bit of pride because not only is it hard for people to ask for help, but then when they think about the extra work that they have to do for a program, [like] coming in for an interview, [they cannot] set aside time to do this. And we stress to folks that we’ll be as accommodating as possible. If they can’t come in person, we’ll do something over the phone. We’ll try to work with them according to their schedule. It can still be very difficult. And part of that might be busyness, but also a sense of pride.

Another frequently-cited factor interview participants perceived as affecting motivation was a lack of trust among NCPs. They felt that some NCPs mistrust the CSAs intentions in connecting them to services, particularly when these referrals result from a recent contempt action filed by the CSA. One caseworker described that some NCPs fear interacting with the child support agency on any topic, describing, “There’s some innate fear of even dealing with the child support agency, thinking that if they even talk to me, they’re going to get in trouble.” Another caseworker elaborated that some NCPs perceive that CSA staff hold negative perceptions about them, reducing their willingness to engage, stating:

I’ve heard a couple of child support workers say that they hear from their noncustodial parents, ‘You probably think I’m a bad parent’ or ‘You probably think I’m a bad person…’ I think a lot of people think that. Like, ‘I’m not calling my caseworker because they’re taking me to court and they think I’m a bad parent.’

From the perspective of some staff, when child support agencies make referrals to employment providers, particularly through court-based enforcement actions, this mistrust can carry over to the employment provider. Described one staff member: “They see these services as an extension of the child support agency, not as a separate body. I think they see anything in their contempt paperwork as all child support… They’re coming after me, they’re making me do all this stuff.”

Beyond or exacerbated by mistrust, staff perceived that some NCPs are unwilling to participate due to resistance to or anger about “being told what to do,” particularly when court-based enforcement is involved; they perceived that some NCPs view these referrals not as help, but as a means of further control. Others noted that feelings of mistrust extend to government-provided services generally; as one director stated on their survey, “Most of our consumers are looking to not participate with government providers due to lack of trust, [and] we have limited for-profit providers in the area to meet mental health, skill building and employment needs.” Some staff and directors also noted that when NCPs have had previous negative experiences with job search or employment services, this can lead to mistrust that services will be effective and reduced motivation to engage. Described one staff member,

The ones that don’t seem to follow through on [employment services] have a negative viewpoint. It’s not necessarily their fault. Maybe they’ve had bad luck in the past. Maybe with having something on their background, they just haven’t had much luck in finding things. I think they have that attitude already, like, ‘I’ve tried it all’ or ‘Why bother’ or ‘I’ve applied at every job in town, and nobody wants me, so, just throw me in jail.’

E. Future Plans for “Connector” Role and Desired Resources to Support This Role

To better understand the direction CSA directors aim to take their agencies in the realm of acting as connectors to other service providers, in interviews and on surveys, directors were asked about their plans and priorities for building and strengthening relationships with employment and other services providers as they look to the future. The survey asked directors, using a five-point response scale ranging from “not at all” to “extremely” important, “When you think about all of your CSA’s priorities for the year ahead, how important do you believe it will be for your CSA to build or strengthen connections with programs and agencies that provide: (1) employment services and (2) other types of supportive services (such as mental health or legal services) that NCPs might need to help overcome employment barriers?” Most directors characterized building or strengthening relationships – both with employment service providers specifically (58%) and other supportive service providers (58%) as “very” or “extremely” important for their agency in the year ahead. In addition to this general sentiment, in interviews, directors and frontline staff articulated specific plans related to building or strengthening employment services referral connections– through activities such as holding job fairs in tandem with local employers or employment service providers, or by taking steps to make employment service providers available to staff at contempt hearings - as well as more general goals to improve coordination and communication between the CSA, employment services providers, and judicial partners.

In interviews, CSA directors and staff shared their perspectives on guidance or resources that could support local efforts to serve in a connector role. One commonly-expressed desire was for the expansion of state- and federally-funded employment service offerings, as well as funding for other supportive services, for NCPs specifically and to meet parent and family needs broadly. They highlighted a need for more mental health and substance use service providers—especially those available at low or no cost to NCPs—and expressed a wish for funding and state support for connecting NCPs to low-cost legal assistance, expungement services, and parenting classes.

CSA directors and staff also cited a need for expanded infrastructure to support efforts to connect NCPs to employment services. They emphasized a desire for a modernized child support computer system—to improve system functionality and automate manual, day-to-day data entry tasks—to allow staff more time for working with parents on complex issues, and expressed a desire for centralized systems to help facilitate information-sharing with partners, as well as a wish for publicly-available, centralized database of employment services searchable across a number of characteristics—such as region, services offered, eligibility criteria or NCP needs—to help CSAs and NCPs to understand local service offerings. Smaller and more rural counties expressed a particular desire for state child support leadership to work with other agencies in advocating for more robust transportation options and improved internet connections – viewed as crucial for job searching in the modern economy.

In interviews, directors and staff also expressed a desire for more resources for CSA internal operations. These included wishes for increased funding, particularly to allow CSAs to hire more staff and reduce caseload sizes. From their perspective, reduced caseloads would help facilitate more intensive and support-oriented case management by allowing staff more time to reach out directly to NCPs and spend time identifying and addressing their barriers to paying support. In interviews and on open-text survey responses, staff and directors also expressed a desire for training and resources to help support local efforts connecting NCPs to employment services, including training guides and policy documents for CSA staff about how to provide services using a more customer-centered approach, as well as best practices for connecting NCPs to services. Directors and staff in several counties expressed that training and outreach related to how CSAs, employment partners, and the courts can work together to connect NCPs to services would be helpful not only for facilitating consistency among staff, but also for stakeholders beyond CSA staff such as courts, employment services providers, and other service providers.

IV. Discussion

The data gathered through this study suggests that CSAs, and the way that they interact with families, are changing. Findings indicate that Wisconsin’s CSAs see connecting NCPs to supports that can help address employment barriers as logical and valuable. They see the potential benefits of helping NCPs access resources that can help address barriers to work, and therefore to paying child support. Many also consider building relationships with community partners who provide services to address barriers as an important priority for the future.

Results from this study broadly align with prior work that has found that for some NCPs, barriers to paying go beyond barriers directly related to employment (Berger et al., 2021; Vogel, 2020), suggesting a need for multifaceted solutions and resources. Further, these findings highlight a fundamental disconnect between many of the issues directors identify as key barriers to NCP employment—such as substance use, mental health, housing, and having criminal records—and services available locally. This study’s findings underscore that the issue of helping NCPs who struggle to find and keep employment requires addressing challenges across individual as well as institutional levels.

Findings from this study also indicate that despite a broadly-held desire to connect NCPs to supportive services, a number of factors can present barriers to collaboration across CSAs and other service providers, and barriers to NCP participation in these services. One of these challenges is sorting out where to send NCPs for help. For CSAs—which have historically operated in a “siloed” manner from other human services agencies—knowing which service providers are available within their community, and what services those providers offer, can be a challenge. Navigating the landscape of providers, and building relationships with those providers, can be challenging, and takes time—a resource directors and staff note is constrained, particularly given large caseload sizes. Directors also highlighted challenges related to engaging NCPs in available services, including overcoming mistrust of CSAs and reluctance to engage in government provided services among some NCPs, a potential lack of desire to engage in services or employment among some NCPs, and service access barriers.

A. Limitations

While findings from this study provide useful insights into county experiences and practices, this analysis has several important limitations. First, data for this study come from CSAs- and primarily directors - in a single state (Wisconsin). Attributes of the Wisconsin context – such as Wisconsin’s population characteristics and needs, resources and constraints, and approach to service provision – differ from other states and may mean responses in other state contexts would differ. Future research could consider perspectives, including that of parents and staff, from a broader array of states and localities.

Additionally, while these findings represent the perspectives of most Wisconsin CSA directors, not all directors participated in the survey, and it is possible that the perspectives and practices of agencies that did not take part differ systematically from the agencies that did.

Further, this analysis draws exclusively on survey data, and does not augment or triangulate findings with external data sources, such as administrative records, that could potentially provide an opportunity for data validation or additional insights, if accessible. Finally, this analysis is purely descriptive. While descriptive analyses can provide helpful insights by statistically summarizing data for a given population on current practices, processes, and perspectives, descriptive analyses are limited in the conclusions that can be drawn from them. These findings are not necessarily generalizable to a broader array of CSAs or directors. Further, this analysis does not attempt to predict relationships between variables, and findings should not be interpreted as causal.

V. Conclusion/Future Implications

As the child support program moves towards incorporating supportive and service-based strategies in addition to traditional enforcement approaches for NCPs who fall behind on their support, learning more about the perspectives, current circumstances and goals of the local programs charged with implementing new policy frameworks into practice – local child support agencies – is a crucial starting point for understanding how policy can support changes in practice. To help inform policy and practice amidst this shift, this study aimed to fill a gap in the literature on CSA leader experiences, views, plans, and needs moving forward.

Findings from this study offer several potential implications for consideration, particularly related to providing supports and resources that could help CSAs serve as connectors to employment services and other supports. The openness of CSAs to serving in this connector role represents a potential opportunity, should state and federal programs aim to expand engagement in “connector” activities. To the extent that state and federal child support programs can provide the resources and guidance CSAs shared through this study – resource mapping, infrastructure investments, modernized data sharing and tracking tools, and training and technical assistance – and ease federal restrictions on how CSAs use child support funding, these supports could help position CSAs to take on a broader “connector” capacity moving forward.

Further, state and federal programs could consider opportunities to provide additional funding for local CSA staff to potentially help reduce caseload sizes and free up staff time for more personalized case management. In addition to resources for staff within CSAs, expanded funding for NCPs-specific programs could help CSAs broaden capacity for serving NCPs with employment barriers—both by providing a place to send NCPs for employment-related supports, particularly in areas with limited other service options, and for connecting CSAs to funding resources for staff specifically focused on helping NCPs with employment barriers.

Finally, system-level barriers, such as lack of transportation infrastructure and lack of service providers within communities, local, state, and federal collaboration is likely required to implement solutions; local CSAs cannot solve these problems on their own. To the extent that federal and state child support programs can advocate for the expansion of services and infrastructure—particularly in areas with significant areas of unmet need—and lead efforts to partner with other key stakeholders whose participation is needed to foster such initiatives, these efforts could help address barriers to service accessibility and connection.

Funding

The research reported in this paper was supported by the Child Support Research Agreement between the Wisconsin Department of Children and Families and the Institute for Research on Poverty at the University of Wisconsin– Madison. The views expressed here are those of the author alone and not necessarily the sponsoring institutions.

One director serves as the director for three agencies; each county was treated as a unit of analysis so the total sample size is 71 (rather than 69).

Response rate calculated using American Association for Public Opinion Research Response Rate 2: https://www.aapor.org/Education-Resources/For-Researchers/Poll-Survey-FAQ/Response-Rates-An-Overview.aspx