Given that human service professionals are often employed in crisis settings, such as social service agencies, they are at increased risk of experiencing high levels of work stress that can lead to burnout, characterized by exhaustion, cynicism, and inefficacy (Saks & Gruman, 2014; Steinheider et al., 2019). Burnout not only affects the human service professionals themselves, but also the employing agencies, by increasing turnover and impairing the quality of services to clients (Glisson & Green, 2011). Thus, the importance of creating human service work environments that facilitate employee engagement, resulting in employee retention and high-quality care (Steinheider et al., 2019).

Conceptualized as a positive state of employee motivation (Kahn, 1990), employee engagement has been associated with organizational outcomes such as productivity, organizational citizenship behaviors, and overall job performance (Harter et al., 2002; Rich et al., 2010; Saks, 2006). Despite the increasing body of research on employee engagement (Bailey et al., 2015; Christian et al., 2011; Macey & Schneider, 2008; Rich et al., 2010; Shuck, 2020), limited research has been conducted in human service specific samples (Akingbola & van den Berg, 2019; Lizano, 2021).

Though starting with the book entitled Job Satisfaction (Hoppock, 1935), and complemented by the development of the Job Satisfaction Survey (Spector, 1985), job satisfaction, a related construct, and motivation with human services staff has been studied for many years. Hoppock (1935) defines job satisfaction as any combination of psychological, physiological, and environmental circumstances that cause a person to truthfully say that they are satisfied with a job. Although numerous studies on job satisfaction have been conducted with human service agency staff including nurses, and others in the healthcare profession, social workers, public health workers, long-term care providers, and palliative care workers (Bhatnagar & Srivastava, 2012; Brown et al., 2019; Harper et al., 2015; Hawes & Wang, 2022; Marmo et al., 2021; Perkins et al., 2023), recent research, including a meta-analysis across public, semi-public, and private sectors, suggests that work engagement is a more robust predictor of employee performance than job satisfaction (Borst et al., 2020; Christian et al., 2011). Thus, the current interest in expanding research exploring the construct of employee engagement in the human services sector, and the importance of this exploratory study. Particularly in the human services field, given the challenges with providing services to clients with complex and high needs, it is critical that we better understand the factors that contribute to employee engagement (Steinheider et al., 2019).

Employee Engagement

Although the first major article to appear in the management literature on employee engagement was Kahn’s (1990) article exploring personal engagement and disengagement, according to Google Scholar, the article was seldom cited during its first 20 years but now has over 1,800 citations (Saks & Gruman, 2014). Kahn’s two qualitative, theory-generating studies of summer camp counselors and members of an architectural firm identified three psychological conditions – meaningfulness, safety, and availability, as descriptive of employee engagement. “Psychological meaningfulness can be seen as a feeling that one is receiving a return on investments of one’s self in a currency of physical, cognitive, or emotional energy. People experienced such meaningfulness when they felt worthwhile, useful, and valuable – as though they made a difference and were not taken for granted” (Kahn, 1990, pp. 703–704). Psychological safety was defined as “feeling able to show and employ one’s self without fear of negative consequences to self-image, status, or career. People felt safe in situations in which they trusted that they would not suffer for their personal engagement” (Kahn, 1990, p. 708). Lastly, psychological availability was described as " the sense of having the physical, emotional, or psychological resources to personally engage at a particular moment. It measures how ready people are to engage, given the distractions they experience as members of social systems" (Kahn, 1990, p. 714).

In the only empirical study to test Kahn’s (1990) theory, May, Gilson, and Harter (2004) found that meaningfulness, safety, and availability were significantly related to engagement. They also found that job enrichment and role fit were positively related to meaningfulness, gratifying coworker and supportive supervisor relations were positively related to safety, while adherence to coworker norms and self-consciousness were negatively related. Additionally, resources available were positively related to psychological availability while participation in outside activities was negatively related (Saks & Gruman, 2014).

A second influential definition of employee engagement is based on the concept of burnout, and engagement being the antithesis of burnout (Maslach et al., 2001). Engagement is characterized by energy, involvement, and efficacy – the direct opposites of the burnout dimensions of exhaustion, cynicism, and inefficacy (Saks & Gruman, 2014). With respect to burnout, one meta-analysis found evidence for the distinctiveness of the engagement construct from burnout (Crawford et al., 2010), while another questioned the distinctiveness of engagement from burnout and raised concerns about violating the law of parsimony (Cole et al., 2012; Saks & Gruman, 2014).

Although both Kahn’s (1990) and Maslach et al.'s (2001) models indicate the psychological conditions or antecedents that are necessary for engagement, they do not fully explain why individuals will respond to these conditions with varying degrees of engagement. A theoretical explanation for the process of employee engagement can be found in social exchange theory (SET; Saks, 2006). SET suggests that obligations are generated through a series of interactions between parties who are in a state of reciprocal interdependence. A basic tenet of SET is that relationships evolve over time into trusting, loyal, and mutual commitments, as long as the parties abide by certain “rules” of exchange (Cropanzano & Mitchell, 2005). Rules of exchange usually involve reciprocity or repayment rules such that the actions of one party lead to a response or actions by the other party (Saks, 2006).

In the 1990s, the Gallup organization issued its first Global Workforce report, which introduced the concept of employee engagement to the business community (Endres & Mancheno-Smoak, 2008; Little & Little, 2006). One of the benefits of the Gallup employee engagement survey, introduced in the report, is that it measures aspects of the workplace that is somewhat under the control of the immediate supervisor; thus, the practical value of the feedback. Harter et al. (2002) followed up on the work initiated by the Gallup organization and was the first to pull data from 7,939 business units across multiple industries to examine the impact of engagement at the business unit level (Shuck, 2020). They defined engagement as “an individual’s involvement and satisfaction with as well as enthusiasm for work” (Harter et al., 2002, p. 269). This relationship of employee engagement with business outcome is referred to as the engagement-satisfaction approach (Kaur, 2017). Subsequent research has shown employee engagement to have a statistical relationship with job satisfaction, commitment, job involvement, task performance productivity, ability, employee retention, safety, and customer satisfaction (Bailey et al., 2015; Buckingham & Coffman, 1999; Christian et al., 2011; Coffman & González Molina, 2012; Rich et al., 2010).

In support of organizations seeking to improve the level of employee engagement, there have been several meta-analyses studies that have identified several antecedents to higher levels of employee engagement (Bailey et al., 2015; Christian et al., 2011; Rich et al., 2010). A key tenet to Kahn’s theory of engagement was based, in part, to Hackman and Oldham’s (1980) notion of critical psychological states. Kahn (1990) proposed that individual and organizational factors influence the psychological experience of work and that this experience drives work behavior (Christian et al., 2011). Drawing on research from job characteristics theory (Hackman & Oldham, 1980), transformational leadership (Bass & Avolio, 1994) and personality (Young et al., 2018), both proximal and distal antecedents, can influence the extent to which an individual experiences a desire to invest their personal energies into performing their work at a high level (Christian et al., 2011; Macey & Schneider, 2008).

Organizational Trust

Central to the network of antecedent conditions facilitating employee engagement is trust (Macey & Schneider, 2008). Engaged employees invest their energy, time, and personal resources, trusting that the investment will be rewarded in some meaningful way; thus, trust in the organization, the leader, the manager, and/or the team, is essential to increasing the likelihood that engagement behavior will be displayed. Trust becomes important even for intrinsically motivated behavior, as the conditions that contribute to the investment of self, require what Kahn (1990) identified as psychological safety. This is the belief people have that they will ‘‘not suffer for their personal engagement’’ (p. 708).

Kahn (1990) stressed the role of supportive and trusting interpersonal relationships at work in the development of employee engagement, and strong empirical evidence implies that social support by supervisors and coworkers is a substantial predictor of employee engagement. One recent study, using a random sample of approximately 375 employees from a variety of industries, was the first empirical research effort to combine measures of ethical environment, organizational trust – as measured through human resource management practices, communications, and values and moral principles, and employee engagement in a comprehensive model (Hough et al., 2015). Prior research has suggested that an ethical organizational environment may lead to higher employee engagement (Demirtas, 2015; Den Hartog & Belschak, 2012; Lin, 2010; Sharif & Scandura, 2014). The most significant finding was that organizational trust fully mediated the relationship between an ethical environment and employee engagement. This significant positive relationship indicates employees’ and managers’ perceptions of how ethical or unethical an organization’s environment directly correlates to their trust or mistrust in the organization. In addition, they show that this trust or mistrust is positively and significantly related to the degree to which employees and managers are engaged with the organization for which they work (Hough et al., 2015).

Closely aligned with organizational trust is the concept of organizational justice (Greenberg, 1987). Employees want to be treated fairly and rewarded equitably by the leaders of their organization for the contributions they make. Organizational justice is comprised of four elements. Distributive justice refers to whether people perceive rewards to be commensurate with contributions made to the organization. Procedural justice is defined as the fairness of the processes that lead to outcomes. Interactional justice refers to perceptions of respect in one’s treatment; and, informational justice speaks to the availability of information in terms of timeliness, specificity, and truthfulness. Much of the early work on organizational justice draws on social exchange theory (Blau, 1964; Colquitt, 2001), with proponents of social exchange theory suggesting that when individuals receive just treatment, they respond in kind by engaging in behaviors that are desirable to the other party (Colquitt et al., 2013; Cropanzano & Mitchell, 2005). Positive effects of these justice judgments on employee engagement (Deepa, 2018; Ghosh et al., 2014), and job engagement are well supported (Haynie et al., 2019; Saks, 2006, 2017).

Supervisory and Coworker Support

Throughout the workplace research conducted by Gallup researchers, both qualitative and quantitative data have indicated the importance of the supervisor or the manager and his or her influence over the engagement level of employees and their satisfaction with their company (Harter et al., 2002). Likewise, in a large study comprising a review of 172 empirical papers, 38 theoretical articles, four meta-analyses, three books, and 14 items from the grey literature, sponsored by the British National Health Service (Bailey et al., 2015), findings suggest a direct link between supervisory support and employee engagement (Freeney & Fellenz, 2013; Othman & Nasurdin, 2013). Additionally, a number of studies found satisfaction with teamwork and perceived organizational support (Brunetto et al., 2013), social support (Freeney & Fellenz, 2013), coworker support (Othman & Nasurdin, 2013), work relationships (Freeney & Fellenz, 2013), and holistic care climate (Fong & Ng, 2012) positively linked with engagement.

Transformational Leadership

Transformational leadership has been associated with employee engagement in a number of recent studies, including in the healthcare (Ree & Wiig, 2020) and service (Agrawal, 2020) industries. Transformational leadership facilitates the development of the fullest potential of individuals and their motivation toward the greater good versus their own self-interests, within a value-based framework (Mary, 2005). This model of leadership is comprised of four components: idealized influence, inspirational motivation, intellectual stimulation, and individualized consideration (Bass & Avolio, 1994). Idealized influence is when leaders choose to do what is ethical rather than what is expedient, and put the interests of the organization before their own. Leaders exhibiting inspirational motivation encourage their employees to achieve more than what was once thought possible through developing and articulating a shared vision and high expectations. Leaders who manifest intellectual stimulation help employees question commonly held assumptions, reframe problems, and approach matters in innovative ways. Finally, individual consideration occurs when leaders pay special attention to employees’ needs for achievement and development and provide needed empathy, compassion, support, and guidance that influence employees’ well-being (Kelloway et al., 2012).

Methodology

This study was conducted in spring 2017 as the class project for a research course in an MSW program in the Northeast. The University Institutional Review Board approved all study protocols, and all participants provided informed consent. Using a prior study examining the association between an ethical work environment and organizational trust on employee engagement as a blueprint (Hough et al., 2015), MSW students collaborated with the professor to create an online survey that was distributed to a convenience sample of staff in human service agencies in the New York City region. Using a participatory action research approach, students were informed about various possible antecedent factors to employee engagement, based on existing general workforce literature, that could be explored, and decided on organizational trust (measured through three subscales – human resource management practices, communications, and values principles), procedural justice, satisfaction with supervisor, transformational leadership, and coworker support. Antecedent variables were carefully selected, based on the existing literature and student personal experience, and intentionally limited, for purposes of maximizing response rates and data quality.

Recruitment

Upon obtainment of IRB approval, students recruited friends and colleagues who were working full-time in a human service agency to participate in the study. Potential study participants were initially recruited using text, e-mail, or phone, and upon acceptance to receive study details, were e-mailed a copy of the informed consent form, along with a link to the SurveyMonkey study survey.

Participants

Using the convenience sampling method, a total of 77 employees from human service agencies participated in the study. Of the participants, the majority (72.7%) were female, and about half (51.9%) were between the ages of 25 and 34. There was racial diversity with the largest representation being Whites (37.7%), followed by Hispanics (29.9%). The majority (59.7%) were direct care staff. With regards to tenure at the organization, the greatest representation were participants who have worked at their organization for between 1 and 3 years (40.3%). Close to half of the participants (46.8%) have worked for their current supervisor for between 1 to 3 years. Given the exploratory nature of this study, the sample being one of convenience, and to protect the anonymity of responses, the decision was made to not collect additional demographic information, such as type of human service professional position or agency, that would possibly allow responses to be linked back to individual participants. Table 1 provides further details of the demographic and employment profile of the respondents.

Measures

All measures, with the exception of coworker support, were psychometrically tested in prior studies. Employee engagement and organizational trust (measured through three subscales – human resource management practices, communications, and values principles) scales were the same as those used in the Hough et al. (2015) study. Procedural justice, satisfaction with supervisor, and transformational leadership measures were identified through the available literature, and coworker support, due to the lack of a psychometrically tested measure, was co-created by the students and professor.

Employee Engagement

The employee engagement scale consisted of a previously validated scale by Buckingham and Coffman (1999). The scale included twelve items measured on a seven-point Likert scale where one indicated strongly disagree, and seven indicated strongly agree. Based on student feedback, minor revisions to the wording on the scale were incorporated. Specifically, the item worded, “In the last seven days, I have received recognition or praise for doing good work” was revised to, “In the last month, I have received recognition or praise for doing good work.” Students felt that one week was too short a time period in which to expect to receive ongoing recognition. And the item “I have a best friend at work” was reworded to, “I have a confidante at work.” Students believed that one’s best friends may not be work colleagues, yet one could have a “confidante” who could be trusted to provide ongoing support.

Organizational Trust

Organizational trust was assessed using the scales created by Vanhala et al. (2011). This scale has three sub-scales: Trust – HRM Practices which included five items; Trust – Communication which included seven items; and Trust – Values and Moral Principles which included four items. Examples of items included “My employer has kept promises made with regards to my career,” “The information that is distributed in our organization is up-to-date,” and “Top management has made it clear that unethical action is not tolerated in our organization.” Similar to the employee engagement scale, a seven-point Likert scale was provided for responses.

Coworker Support

Due to the lack of an available psychometrically tested scale to assess for level of coworker support, students contributed to developing a new measure for purposes of this study. The five items in the scale were: “I am not afraid to share work-related opinions with coworkers,” “My coworkers give me credit for work ideas/tasks I contribute,” “I can rely on my coworkers for support,” “My coworkers deliver on work commitments they make,” and “My coworkers contribute their fair share in the department.” As with some of the other study measures, a seven-point Likert response scale was used.

Satisfaction with Supervisor

To measure the level of satisfaction with the immediate supervisor, the empirically derived Satisfaction with My Supervisor Scale (SWMSS) was administered (Scarpello & Vandenberg, 1987). The scale was previously demonstrated to have convergent, discriminant, predictive, and content validities (Scarpello & Vandenberg, 1987). The 18-item scale used a five-point Likert scale and, based on student feedback, two items were reworded for perceived improvements. Specifically, the question “My supervisor’s backing me up with other management” was revised to “My supervisor supporting my decisions with other management,” and “The frequency with which I get a pat on the back for doing a good job” was revised to “The frequency with which I receive praise for doing a good job.”

Procedural Justice

To measure procedural justice, a six-item Formal Procedures subsection of a larger scale that also measured Distributive and Interactional Justice (Niehoff & Moorman, 1993) was used. The scale was based on one previously employed by Moorman (1991) and had reported reliabilities of over .90 for all three dimensions. All items used a seven-point response format. For the items to be more applicable to the study population, the phrase “general manager” was replaced by the phrase “department head.” Thus, for example, the question “Job decisions are made by the general manager in an unbiased manner” was revised to “Job decisions are made by the department head in an unbiased manner.”

Transformational Leadership

Transformational leadership was measured using the Global Transformational Leadership Scale (GTL; Carless et al., 2000). Participants were asked to rate the leadership style of the highest leader in their organization based on a five-point Likert scale. Examples of items are: “Communicates a clear and positive vision of the future,” and “Treats staff as individuals, supports and encourages their development.” Carless et al. (2000) found the GTL to have a high degree of convergent validity with the more extensive and established Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire (MLQ; Avolio et al., 1995).

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were conducted to describe the sample demographics and employment status. Pearson correlation was used to measure the degree of relationship among employee engagement and other key variables. The independent sample t-test was employed to understand whether there is a difference in the mean of the key variables between the demographic and employment status groups. Hierarchical linear regression was conducted regressing employee engagement on the five antecedent variables and six control variables; specifically, age, gender, race, direct care position or not, tenure at the organization and with the current supervisor. The Sobel test was used to determine the degree of mediation, including both direct effects and indirect effects. SPSS 25.0 was used to conduct the statistical analysis for this study.

Results

Descriptive statistics

Table 2 presents the means and standard deviations of the key study variables used in this study. The Cronbach’s alpha reliability for the self-developed coworker support scale is .857, which is good.

Bivariate analysis

Table 3 presents the inter-scale correlations among the key variables in this study. The employee engagement, organizational trust, coworker support, satisfaction with supervisor, procedural justice, and transformational leadership variables are significantly correlated with each other (p <.01).

There is no significant difference in the mean score of key variables across gender (female vs. male), race (white vs. non-white), age, position (direct vs. non-direct care), or tenure with the current supervisor. However, respondents who have worked at the organization for less than 1 year demonstrated significantly higher scores in organizational trust (M = 85.8, SD = 13.0 vs. M = 76.3, SD = 18.2, t = 2.0, p = .048), procedural justice (M = 31.4, SD = 5.8 vs. M = 26.2, SD = 9.1, t = 2.2, p = .030), and organizational trust (M = 30.4, SD = 4.7 vs. M = 25.1, SD = 8.1, t = 2.5, p = .013) compared to those who have worked for 1 or more years.

Multivariate analysis

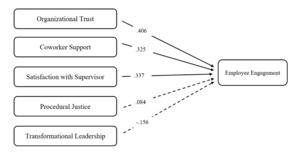

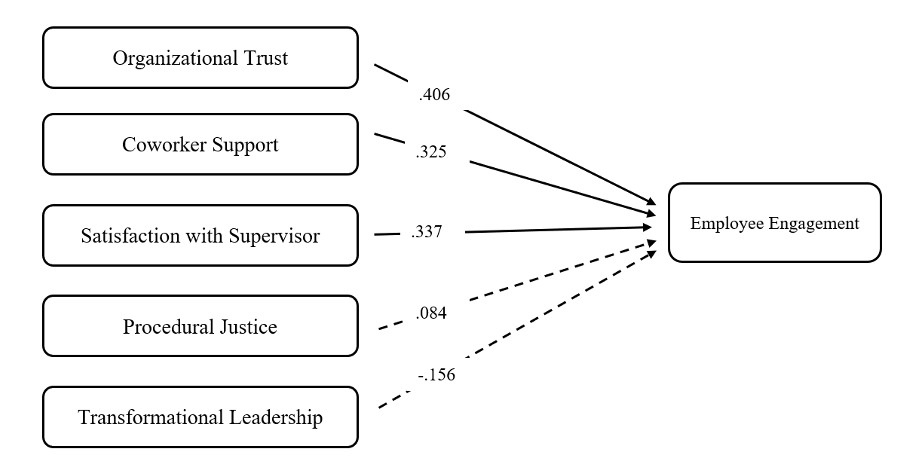

A four-stage hierarchical multiple regression was conducted with employee engagement as the dependent variable. The demographic and employment status variables were entered at stage one of the regression to control for age, gender, race, direct care position or not, tenure at the organization and with the current supervisor. Organizational trust was entered at stage two, coworker support and satisfaction with supervisor at stage 3, and procedural justice and transformational leadership at stage 4. Table 4 presents the results from the hierarchical regression model. After controlling the demographic and employment status variables, the organizational trust, coworker support and satisfaction with supervisor were consistently significant predictors of employee engagement, while neither procedural justice nor transformational leadership were significant predictors of employee engagement. Together all the independent variables accounted for 72.3% of the variance in employee engagement.

Specifically, employees who score 1 point higher in organizational trust tend to score 0.285 points higher in employee engagement; employees who score 1 point higher in coworker support tend to score 0.775 points higher in employee engagement; and employees who score 1 point higher in satisfaction with supervisor tend to score 0.241 points higher in employee engagement, after controlling for age, gender, race, employment status, procedural justice and transformational leadership.

Figure 1 presents the standardized beta coefficients for the key variables in the final linear regression model. Standardizing variables before running the regression puts all of the variables on the same scale, which makes it possible to compare the magnitude of the coefficients to see the relative impact of the predictor variables on the dependent variable. Results indicate that organizational trust shows the largest effect on employee engagement, followed by the effects of satisfaction with supervisor, and coworker support.

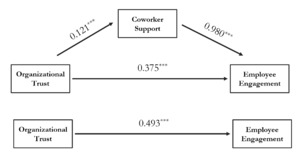

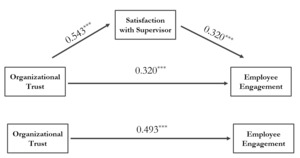

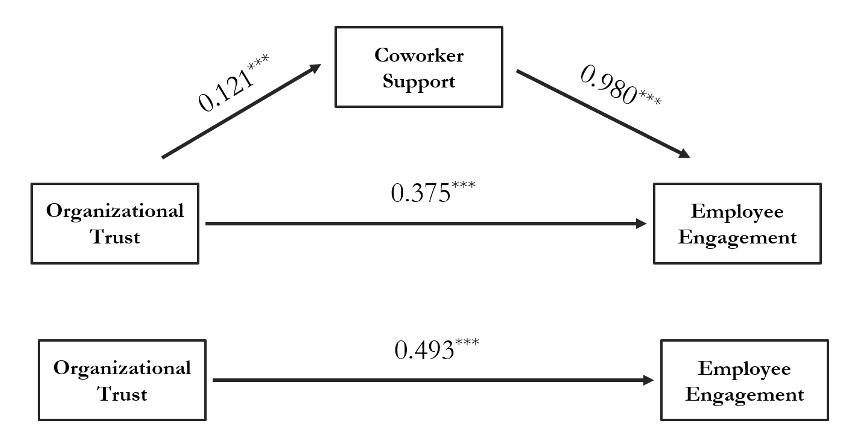

Mediation effect

Figures 2 and 3 present the results regarding the mediating roles of coworker support and satisfaction with supervisor in the relationships between organizational trust and employee engagement. The results show that coworker support and satisfaction with supervisor partially mediated the effect of organizational trust on employee engagement. Effects of organizational trust decreased from 0.493 (direct effect without mediation) to 0.375 (effect after controlling for mediation), suggesting that approximately 24% of the effect of organizational trust on employee engagement is mediated by coworker support. The mediation effect of satisfaction with supervisor between organizational trust and employee employment was shown to explain 35% (decrease from 0.493 to 0.320) of the direct effect. A Sobel test was performed to estimate the significance of the mediation effects and it confirmed that both mediations were significant (p =.002).

Discussion and Practice Implications

Organizational Trust, Leadership Practices

This study explored antecedent factors (both proximal and distant) that contributed to employee engagement in the human services sector, using a convenience sample of staff in human service agencies. Several antecedent factors were explored, including organizational trust (human resource management practices, communications, values principles), procedural justice, satisfaction with supervisor, transformational leadership, and coworker support. The main finding from the multiple regression was that organizational trust, satisfaction with supervisor, and coworker support were consistently significant predictors of employee engagement, but not procedural justice nor transformational leadership, and together all the independent variables accounted for almost three-quarters (72.3%) of the variance in employee engagement. Further linear regression produced the result that organizational trust shows the largest effect on employee engagement. This finding is consistent with previous research that demonstrated the foundational nature of trust to facilitate employee engagement (Macey & Schneider, 2008); and supports the previous model of organizational trust, measured through human resource management practices, communications, values/moral principles, and degree of employee engagement (Hough et al., 2015).

Leaders in human service organizations would be well advised to foster organizational trust at all levels, i.e., staff/team, supervisor/manager, as this is likely to result in engaged employees. Employee engagement has known benefits on the organizational level, including increased productivity, organizational citizenship behaviors, and overall job performance (Harter et al., 2002; Rich et al., 2010; Saks, 2006). These favorable outcomes are salient and relevant for leaders in human service organizations given widespread increased service demands and inadequate staffing resources (Hopkins et al., 2014). An interesting finding related to organizational trust was that respondents who worked at their organization for less than 1 year demonstrated significantly greater likelihood of higher scores in organizational trust. This finding may suggest that newer employees are in the “honeymoon” phase of work and may not have yet encountered trust issues within their organizations. Managers and supervisors may want to pay attention to this finding, because if they are able to maintain this initial high level of trust with employees, they may reap benefits longer term with employees continuing to invest their energy, time, and/or personal resources, trusting that the organization will meaningfully reward this. Previous research has found that managers and supervisors recognized investing in relationships and being trustworthy was foundational to their leadership practice (Vito, 2019).

Satisfaction with Supervisor, Selection and Training

The results also demonstrated a mediation effect between organizational trust on employee engagement, as the total effect of organizational trust can be partially explained by its effect on satisfaction with supervisor (35%), and coworker support (24%), which in turn affects employee engagement. This finding supports previous research on the importance of supportive and trusting interpersonal relationships with supervisors and managers on the development of employee engagement (Harter et al., 2002; Kahn, 1990). Indeed, others have found a direct link between the support offered by supervisors with employee engagement (Freeney & Fellenz, 2013; Othman & Nasurdin, 2013); and previous managers and supervisors discussed being strength-based and supportive in their leadership practice to motivate, empower and mentor employees (Vito, 2019). The importance of the supervisory relationship is a foundational human services practice and the positive impact on employees’ well-being and learning has been well documented. Effective supervision and positive supervisory relationships increase workers’ effectiveness and commitment and improves client service delivery and outcomes (Bogo & McKnight, 2005; Mor Barak et al., 2009). These findings are important because supervisors and managers, along with co-workers, are in positions of closest proximity to employees and are therefore likely to have the greatest influence on them. The finding of proximal influence between staff, supervisors and colleagues has similarly been reported during organizational change (Esaki et al., 2014).

The mediating effect of satisfaction with supervisor has implications for the selection and training of supervisors and managers, and leaders should give thoughtful consideration as to who is best suited for these key positions. Supervisors and managers with well-developed emotional intelligence (self-awareness, self-regulation, empathy, interpersonal skills) have the capacity to develop trusting relationships (Ingram, 2013). These skills may be prioritized during the hiring process and supported during training and ongoing mentoring; as coaching and mentoring are related to employee engagement (Saks, 2017). Ensuring that supervisors and managers have the suitability for developing trusting relationships with their employees is a wise investment for leaders in human service organizations. Previous research has demonstrated a relationship between employee engagement and multiple positive outcomes, including job satisfaction, commitment, task performance, productivity, ability, retention, safety, and customer satisfaction (Bailey et al., 2015; Buckingham & Coffman, 1999; Christian et al., 2011; Coffman & González Molina, 2012; Rich et al., 2010). Moreover, employee engagement produces greater energy, involvement, and efficacy; unlike employee burnout, which includes exhaustion, cynicism, and inefficacy (Saks & Gruman, 2014). Previous research has demonstrated that a lack of supervisory and organizational support was a significant predictor of employee burnout and secondary traumatic stress (Handran, 2015). Given how costly employee burnout and turnover is to both individuals and organizations (Steinheider et al., 2019), it is wise for leaders in human service organizations to invest proactively in supervisors and managers who have emotional intelligence skills and will forge trusting relationships with their employees.

Coworker Support, Team Building

Coworker support was also found to be a mediating variable between organizational trust and employee engagement, and others have found a direct link between coworker support and employee engagement (Freeney & Fellenz, 2013; Othman & Nasurdin, 2013). This finding has implications for team building within human service organizations. Previous research has found a link between perceived organizational support and satisfaction with teamwork (Brunetto et al., 2013); supervisors and managers considered teamwork foundational, building mutual support in teams, developing respectful relationships and team processes for managing conflict (Vito, 2019). Organizations that hire employees who are team players and capable of building trusting peer relationships can build healthy and supportive teams, thereby fostering coworker support and increasing employee engagement. In particular, positive affectivity (emotions) has been strongly linked to employee engagement, and pre-employment strategies such as personality-based assessments may be used during the employee selection process (Young et al., 2018). These suggestions have implications for producing beneficial service outcomes. Given the challenges with providing services to clients with complex and high needs, it is critical to understand the factors that contribute to employee engagement in order to deliver high-quality care (Steinheider et al., 2019). Addressing individual factors and team building and encouraging positive coworker support are therefore important considerations for leaders in human service organizations.

Procedural Justice, Transformational Leadership

Procedural justice and transformational leadership were not found to be significant predictors of employee engagement. This finding contradicts previous research on transformational leadership that was associated with employee engagement in the healthcare (Ree & Wiig, 2020) and service (Agrawal, 2020) industries. This finding may be explained by the concept of distal relationships, as leaders in human service organizations are more distant to employees than supervisors and may therefore have less influence on developing trusting relationships that are pivotal to employee engagement. Previous research has found that leaders in distal positions were less likely to demonstrate desired behavior, which may have been due to a lack of communication and interaction with employees or a power dynamic and lack of modelling desired behaviors (Esaki et al., 2014). Other researchers have discussed the need for leaders to be reflective, aware of their positional power, and balance this through both the logical and emotional tasks of leadership (Vito, 2019). Procedural justice focuses on fair processes that impact outcomes, and it has been previously found to have a positive effect on employee engagement (Deepa, 2018; Ghosh et al., 2014; Saks, 2017). The current results did not find procedural justice to be a significant predictor of employee engagement, although it is closely related to the concept of organizational trust, which was significant and may have confounded the results.

Research Implications and Limitations

This exploratory study adds to our knowledge of employee engagement in human service organizations, as there is minimal empirical research that has focused specifically on employee engagement in nonprofit organizations (Akingbola & van den Berg, 2019). Organizations that desire to improve employee engagement may want to decide which resources (e.g., social support) and processes (e.g., trust perceptions) are important to measure, and what subsequent changes may be made at both the individual and organization levels (Saks, 2017). Included in the analysis may be a review of existing human resource management policies and practices, and plans for revisions in support of elevating employee engagement.

There were several limitations with the study that can be addressed in future research. First, this was a limited sample, and a larger more representative sample would strengthen future findings. Additionally, the study was cross-sectional in nature and did not measure for causal inference of the antecedent variables of employee engagement. Lastly, the employee engagement measure was not based on Kahn’s definition and may be more reflective of working conditions closely associated with employee engagement. A broader longitudinal study could be undertaken in future research to test the causal inference of the antecedent variables identified in this study, as well as to investigate the impact of employee engagement on employee well-being and organizational outcomes, including client outcomes.

Author Note

We have no conflict of interest to disclose.