What is Motivational Interviewing?

Motivational interviewing (MI) is an evidence-supported style of communication used across many fields of human services, including addiction treatment, social work, healthcare, education, and criminal justice (Miller & Rollnick, 2023). This style of communication is designed to support increased internal motivation to prepare for and engage in a variety of behavioral changes that an individual may prioritize. Rather than a form of persuasion, MI focuses on a person’s own reasons for changing and explores their ideas for how they might do so, with an emphasis on respect for each person’s right to make their own decisions for themselves. The interviewer’s role in an MI conversation is to listen with empathy and curiosity about the individual’s own priorities and reasons for change and ideas for doing so, all while providing an environment of compassion and respect. There is a substantial body of research supporting the efficacy of MI across many fields. An article reflecting on the evolution of MI (Miller, 2023) reports that between ⅔ to ¾ of nearly 2,000 clinical trials and over 200 meta-analyses and reviews have found benefits to this approach.

Why MI for Human Services Students in a Community College Setting?

Human Services programs around the country are designed to support students in gaining competency in the core elements of the helping process originally identified by Carl Rogers: communicating accurate empathy, positive regard, acceptance of each person’s inherent worth, developing shared goals, and genuineness (Rogers, 1959). These qualities have been found across 70 years of research to predict positive client outcomes (Miller & Moyers, 2021). These skills are operationalized in MI, along with an emphasis on evoking the individual’s own motivations for change and ideas about how to move towards their goals (Miller & Rollnick, 2023). A community college human services program is an ideal environment for training future helping professionals in MI. MI can be utilized by a variety of human service professionals and requires no special licensure or educational degree (Miller, 2023). Of the students completing their Associate of Arts (AA) degree in human services in our program, about half transfer to four year colleges, majoring in human services or social work (Bimbi, 2021). Anecdotally, those who pursue full time employment report being hired as social and human service assistants, patient navigators, and community outreach workers in community-based organizations, drug treatment or harm reduction programs, hospitals or clinics or other social service agencies (Juline Koken, personal communication). Training in MI is highly desirable for employment in these arenas, and also prepares students well for further training in social work or counseling at the four-year college and beyond. Many of our students have reported that their MI training gained through our program was a key factor in their successful employment search (Juline Koken, personal communication).

However, it appears that MI training may be uncommon at the community college level. Published literature on MI training for students enrolled in a community college program is scant - we were able to identify one paper, which describes piloting this approach in a dental hygienist program (Curry-Chiu et al., 2015). An informal inquiry on an MI training listserv, conducted by the second author, received only one report of MI training implementation at a community college, as part of a community health worker program, with the remainder of replies describing MI training in four-year colleges or graduate programs.

Increasing Demand for Skilled Human Services Professionals

Since the advent of the COVID 19 pandemic, there is an urgent need for increasing the number of mental health professionals of diverse backgrounds; the Handbook on Occupational Outlook suggests as of October 2022 that there is a 20% increase in demand for mental health counselors (Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor, n.d.). A recent report by the Commonwealth Fund (2023) stated that “as of March 2023, 160 million Americans live in areas with mental health professional shortages, with over 8,000 more professionals needed to ensure an adequate supply”.

Recruiting community college students from human services programs allows for the training and preparation of a multi-lingual, culturally diverse behavioral health workforce. Incorporating MI training into human services programs provides students with the opportunity to gain a highly desirable ‘micro-credential’ as part of their college education. When students are able to connect their clinical aspirations with their college education, we believe they may be more likely to persist to graduation.

MI Training in the Classroom: Our Approach

Our program (which currently serves about 200 students) is housed within LaGuardia Community College, CUNY, a Hispanic serving institution in the most diverse county in the continental United States (https://www.laguardia.edu/about/). The Human Services Program has a generalist focus with a strong emphasis on the skills necessary to help people through offering culturally competent care, services, information, and resources. MI has been integrated into our core curriculum so that students are introduced to the practice of MI in their first human services class (HSS 101), then receive an entire semester of MI training in our Interviewing and Counseling class (HSS 216), followed by their fieldwork internship (HSS 290).

MI in the Classroom: Overview of Integration of MI in the Human Services Curriculum

MI Training in the Classroom: Our Interviewing and Counseling Course

The Interviewing and Counseling course (HSS 216) is a required core class in our Human Services program and follows best practices for training in MI (Miller, 2023). In addition to traditional weekly lectures and discussions providing an overview of the counseling profession, the class incorporates a weekly two-hour practice lab. Student learning is supported through presentation of MI videos (The Change Companies, 2013) to explore specific aspects of MI skills, instructor demonstration and modeling, and of course, student practice. Students begin with simple practice of reflective listening skills, then gradually add in the more technical elements of MI practice - evoking and reinforcing change talk, softening sustain talk, moving into planning, and how to offer suggestions or information in an MI consistent fashion. In addition to weekly practice with feedback from their student peers and instructor, students complete four recorded MI roleplays over the course of the semester and receive feedback from their instructor using a research-tested instrument, the MI Coach Rating Scale (Naar et al., 2021, 2022, 2023).

The four recorded roleplays build in complexity over the course of the semester, and each asks the student to roleplay a provider in a profession that graduates of a community college human services program could gain employment within. The first roleplay is a conversation between a community college student, with the MI provider playing the role of a student peer advisor. Skill targets include listening with empathy and demonstrating basic reflective listening skills such as asking open questions and offering ‘simple reflections’ (a statement that repeats or paraphrases what the student seeking advisement has said).

In the second roleplay, the student MI provider plays a patient navigator working in a hospital or clinic that cares for people living with chronic illnesses (such as HIV, asthma or diabetes). During this roleplay students continue to practice reflective listening, now with a focus on evoking patient change talk (patient statements expressing a desire to take care of their health, reasons for medication adherence, or ability to engage in a treatment regimen, for example) regarding health goals. If patients describe barriers to engaging in self-care behaviors, or a lack of confidence in their ability to do so, the MI provider may demonstrate skills in ‘softening sustain speech’ such as reinforcing the patient’s right to make their own decisions, empathy for barriers, and curiosity about how the patient might overcome such barriers.

The third and fourth roleplays are designed to simulate sessions one and two of a brief alcohol counseling program for people mandated by the criminal justice system after an arrest for public intoxication. During these roleplays the student MI provider plays the role of a substance use counselor, incorporating the MI skills (reflective listening to demonstrate empathy, evoke change talk and soften sustain talk), while moving into the planning process if the client is willing and ready to do so. At this stage, the student MI provider may offer options or information for the client to consider if they give consent.

As the semester progresses and students gain competence in the MI skills, more advanced practice goals are introduced, such as offering more reflections than questions, and more complex reflections (statements reflecting client speech that go deeper than a basic repeat or paraphrase). The goal of strengthening these micro-skills is to gain competence in shaping a conversation around the client’s own priorities and goals and moving towards readiness or commitment to change in collaboration with the client. This iterative process helps students build confidence and begin to develop their own voice as aspiring helping professionals.

Students may also listen to their own recorded role plays for self-evaluation, and with their permission, occasionally selected student roleplays are shared with the class to showcase skills students have acquired. By showcasing examples of quality student MI, students learn from each other and begin to recognize that students may become MI experts themselves with practice. By the end of the semester, students have received 24 hours in MI instruction from a well-qualified MI instructor, with feedback on four recorded practice samples, and all receive a certificate of completion. Students are encouraged to add MI as a micro-credential to their resumes. The interviewing and counseling class is a prerequisite for their required internship and is intended to prepare students to use their MI skills in a social service or educational placement.

MI in the Classroom: Getting Started

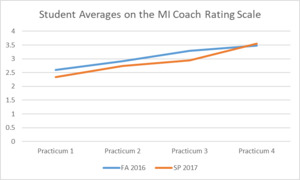

In the Fall of 2016, our Human Services program introduced the Interviewing and Counseling course with the MI lab for the first time. For this initial course offering, to support training of an adjunct faculty who had MI experience but not training experience, the second author (who is a member of the Motivational Interviewing Network of Trainers) led two combined MI labs with the assistance of the adjunct instructor, in order to support their gaining competence in MI training. The following semester, Spring 2017, the adjunct was prepared to lead their own section of the course and did so. Student learning outcomes were positive and presented at the International Conference on Motivational Interviewing (ICMI) in the summer of 2017, with the assistance of one of the students (Karla Chinchilla) who had completed the course and assisted with data preparation and analyses (Koken et al., 2017). The table presented below displays the student averages on the roleplays as assessed by the MI Coach Rating Scale (MICRS) during the first two semesters the course was run. Over the two semesters of data presented here, average student proficiency increased as the semester progressed as evidenced by higher scores (one being the lowest and four being the highest) on the MICRS at each of the four feedback points:

MI in the Classroom: Keeping it Going Through Faculty Development

Continuing to be able to offer the Interviewing and Counseling course requires faculty and staff who have expertise in MI and competence in training others in this style of communication. In previous years we have addressed this challenge by seeking faculty and adjuncts who come already trained in MI to teach the class. Recognizing the need for sustainable implementation of MI in our program, in the preceding academic year, the second author facilitated a year-long training in MI for the faculty and staff of our department of Health Sciences (which contains the Human Services program) in which the first author participated.

The faculty development program followed best practices in training in MI (Miller, 2023) beginning with a 12 hour long introductory training, after which each trainee submitted a series of three practice recordings, which were MITI coded using the MITI 4.2 coding system (Moyers et al., 2014). Each trainee received personalized MITI feedback on their practice sample after each sample was submitted, and the trainees met as a group for three rounds of coaching. This helped to establish competence in MI before the rollout of the 18-hour long training of trainers, during which each trainee practiced facilitating aspects of an introductory MI training. The training program was broken into two-hour segments over the course of the academic year and included human services faculty as well as faculty from other disciplines (physical therapy assistant, occupational therapy assistant, therapeutic recreation, public health, and nursing). This helped to increase the number of faculty in our Human Services program qualified and prepared to teach the interviewing and counseling course. We were also able to fold in information about MI and brief experiential MI activities into our Introduction to Human Services courses following this training, supporting expanded implementation of MI throughout our core curriculum. Incorporating MI into our introductory courses helps students connect their education with their professional aspirations from the beginning of their college experience. This can be motivating to engage and retain students from early on in their educational journey.

MI in the Classroom: Our Fieldwork Program

Our Human Services fieldwork program is completed by students toward the end of their tenure at the college after the Interviewing and Counseling class and is considered our program’s capstone course. During the fieldwork course (HSS 290) students complete a 72-hour placement, along with a weekly seminar and studio hour. Students are expected to practice their MI skills in their internship setting, and as part of their coursework they complete assignments asking them to describe the ways in which they are incorporating the aspects of MI (such as reflective listening, empathy and genuineness) into their work with clients.

Fieldwork placement settings include after school programs, residential and housing programs, harm reduction programs, early childhood centers and older adult service centers. The experience is an opportunity for students to engage in the helping process. Students navigate the myriad of challenges and needs of people while building helping relationships, practicing empathic listening, gathering information, forming action plans, implementing those plans, and evaluating and documenting their work.

This is when the real learning takes place. Motivational interviewing is the way of being with clients. Through this they learn the value of spending time establishing trust and rapport which allows the student and client to move forward in a productive and helpful manner. Students realize the importance of investing early on in the relationship even when time is of the essence. As suggested by Miller and Rollnick (2023):

so often in human services, far too little time and attention are devoted to engaging. The urge to get right down to business may be powerful due to time pressures and caseloads, but sacrificing engagement is unwise if what you hope to do is facilitate positive change and growth (p. 53).

In the course seminar, students work in small groups reflecting on their internship experiences, connecting their experiences to their coursework and discuss issues that surface while on internship. Students offer each other feedback and support as they reflect on how their MI practice is evolving through their internship experience. Students along with the seminar instructor try to model the behaviors consistent with a person-centered approach, listening for change talk and utilizing the very same skills they are practicing in the field. Students often report feeling very proud of what they have learned and can do because of their training in MI, regularly sharing that this was one of the best parts of their educational journey at the college.

MI in The Classroom: Student Reflections

Student Alumnus: Karla Chinchilla

While completing my undergraduate degree at LaGuardia Community College I was enrolled in HSS216, a new program course for the Human Services major. As the first cohort to take the course, I was worried that this was going to be too much for myself and some peers. However, the lab provided the space to practice the MI skills we were being introduced to. It felt like we were learning a new language. Our professors stressed that we lean into the process, because in the field, we are going to be expected to problem solve while being pulled in every direction the agency may need. Learning MI was going to enhance our ability to communicate with a client. As helping professionals, we will always have our ‘MI Tool Kit’ to assist us in making the most of our time with a client.

The MI skills we focused on in the lab helped us not only identify change talk but elicit it. Engagement and collaboration with the client will only aid in the helping process, and this came full circle in my first post-graduate role as a Health Educator. I was assigned a caseload that led me to encounter scenarios that were similar to what we had practiced in our lab course. In interventions where I felt stuck, or that my client was pulling away, I used MI skills to re-engage the client. The use of affirmations landed, and an open-ended question was very effective when working with different age groups; I was able to observe the change in their body language and tone. I felt confident in my abilities due to the work learned through HSS216. Two years after completing my associate degree, I found that I was drawing on what I had learned in my HSS 216 class in order to successfully complete my senior year internship for my bachelors.

Student Alumnus: Landon Ranchor

The HSS 216 class with the MI lab was one of my required courses while I was in my first semester of my senior year at LaGuardia Community College. The course fascinated me from the start as it encouraged me to learn a new approach to engaging with clients while simultaneously challenging me to unlearn habits like advice giving. The professor was incredibly patient towards us and provided detailed and valuable feedback on our process recordings. Due to the rigorous nature of the course, I felt challenged beyond any course I had taken up to that point. However, I found comfort and felt supported that though I may not be an MI expert just yet, to keep practicing, keep trying, and that I would someday be able to utilize MI in future endeavors with clients at internships and job placements.

One of the most valuable skills I learned from MI was the importance of the pause. While at first it felt uncomfortable and challenging for me to pause and process what a client just said to me in front of them, I quickly realized how beneficial of a skill it is. The silence allowed me to use body language and other active listening skills to demonstrate to the client that I was empathizing, processing, and non-judgmentally supporting them.

MI proved particularly useful in my internship placement while obtaining my bachelor’s in social work at my senior college. I was in an environment supporting college adolescents in the LGBTQIA+ community. This community is at risk for several mental health challenges, substance misuse, suicidal ideation, and sexual and gender-based harassment and assault. Due to the intimate nature of these issues, establishing rapport and trust quickly while entering their space was of high importance to me. In spite of not having any further MI training since my LaGuardia courses, I reflected and relied on all I learned in MI to ensure that my group and individual sessions with clients were as productive and respectful to the individual’s autonomy as they could be.

The skills I learned in MI served to be mutually beneficial for the clients and myself because it allowed trust to be built and helped the clients feel safe to share their hardships and struggles. They quickly learned I wouldn’t give them advice, judge them, or try and tell them what to do. The sessions were a safe space for them to express themselves authentically because transparency and respect for their autonomy was always at the forefront of our work together. The clients had a positive reaction to our interactions, many of them began to gravitate towards me and began to frequently request to talk to me privately. Currently, I am pursuing my MSW and look forward to utilizing and enhancing my MI skills during my internship placement. I hope to continue more MI training in the future as I have found a love for it and can see how much of an impact it has made on my clients and myself.

MI in the Classroom: Meeting Implementation Challenges

The COVID-19 pandemic required a sudden shift to online instruction. While challenging, we found that we were able to successfully provide MI training using online modalities (such as Zoom or Blackboard Collaborate Ultra) where students met virtually and could engage in discussions and roleplay much as they would in an in-person classroom. However, many students were logging into class from environments that may not be ideal for training in MI, such as a home where there may be many people present, or, occasionally, students have logged in from cars while driving, or even from work. Many students are reluctant to turn on their video cameras (this is now a requirement built into the course syllabus), which can interfere with practicing communication skills - without being able to see facial expression or body language, conversations can be more difficult. While our program has since transitioned back to a mix of online and in-person courses, many students have been reluctant to return to in-person courses.

MI in the Classroom: Expanding Accessibility

We believe in the potential and the power of MI in the community college classroom. A focus of our work is in making this approach as accessible as possible. Representation matters when training a highly diverse student body such as ours at LaGuardia Community College. Expert examples of MI practice by racially and ethnically diverse MI providers featuring an array of care environments with diverse patients / clients are needed. Too often available MI training resources fail to reflect the rich diversity of our communities. We hope to create materials reflecting this diversity for our own students and we hope many other MI professionals will join us in this effort. The potential to develop open educational resource (OER) materials to support MI learning in community colleges and elsewhere is significant; this Spring, we will begin transitioning our interviewing and counseling class and our fieldwork class to an OER format.

We have several ongoing and future goals for continuing to implement high quality MI training for our students. These include training faculty and staff in MITI coding to measure MI learning outcomes, which we are implementing in the Spring of 2024. Out of a desire to make MI as accessible as possible to the wider college community, as of this Fall we switched our assessment of MI learning outcomes from the MICRS to the MITI, which is nonproprietary.

We would also like to increase the number of fieldwork placements within programs that explicitly integrate MI into their service provision. This would include MI supervision of our students while they are completing their fieldwork to support MI fidelity. We would also like to create a mechanism for surveying students post-graduation to learn more about how their MI training connected with their academic and professional goals.

Ongoing Evaluation of MI Implementation

It is critical to evaluate student learning outcomes and fidelity of MI training to ensure that our program continues to offer a high-quality education. In our program this is done in several ways. First, we continue to collect data in each interviewing and counseling course to monitor student learning outcomes in MI. This Fall we switched from the MICRS to the MITI 4.2 to increase accessibility of the instrument (the MITI is not proprietary and is more commonly used than the MICRS, potentially allowing us to compare our student outcomes with other programs in the future). Student evaluations of the course have been highly positive across semesters and instructors since we initially began implementing the interviewing and counseling class in 2016. Our most recent Periodic Program Review (an unpublished evaluation and report produced about every five years for our college which includes an outside reviewer) in 2021 identified integration of MI into our curriculum as a distinguishing feature (Bimbi), bringing our program into the forefront of best practices for human services training. We hope that other community college human service programs will publish their experiences implementing MI, so that as a community we can learn from each other. Finally, we are planning to create a mechanism for more systematically tracking educational and career outcomes for our program graduates to further evaluate the impact of our MI curriculum.

In Conclusion

In the years since we initially began offering the Interviewing and Counseling course with the MI lab, we have seen many cohorts of students graduate and transfer to four-year programs in social work, counseling, community health and other human services fields. We have received feedback from former students about the utility of the MI skills in their continuing education, and many have also reported that this credential was directly linked to gaining employment in the field. It is our hope that the model described in this paper may be of use to other community colleges in implementing MI training in their human services programs to provide this valuable credential to students and prepare them for further success in their professions.